Marco Di Lauro è nato a Milano nel 1970. Spinto dalla madre, comincia a praticare la fotografia giovanissimo, passione che crescerà nel tempo.

Dopo gli studi di storia dell'arte e giornalismo si diploma in fotografia allo IED, a Milano. Da allora la sua carriera di fotografo si è definita e sviluppata: dai primi reportage da freelance alle collaborazioni con le agenzie e testate internazionali, coprendo spessissimo zone di guerra, conflitto o calamità naturali.

Dal 2002 fa parte di Getty Images.

Sei un reporter impegnato in zone di conflitto e di emergenze umanitarie e ci interessa iniziare da questa tua esperienza. Innanzi tutto: perché hai deciso di fare il reporter lavorando in questi contesti?

Credo che questa mia scelta sia parte di un percorso personale, iniziato all’età di 18 anni, quando lavoravo per la Croce Rossa Italiana come paramedico, a Milano, città dove vivevo al tempo. Quella è forse la mia prima esperienza legata al sociale, e lì mi resi conto che volevo fare un lavoro che avesse anche una funzione sociale, oltre che farmi guadagnare dei soldi alla fine del mese… Lavorare come paramedico mi ha insegnato molto sulla gente, sui problemi della società in cui vivo. Quando poi mi iscrissi a Lettere e Filosofia, con l’idea di fare il critico d’arte, mi appassionai sempre di più alla composizione dell’immagine, alla luce, alla pittura: avevo già l’hobby della fotografia, che mi aveva trasmesso mia madre fin da ragazzino, e avevo una grossa curiosità per quello che era la geopolitica, per il “resto del mondo”…

Qual è il senso e il valore di questo lavoro oggi, soprattutto di fronte alle mutazioni tecnologiche e del mercato? È cambiato - in qualche modo - il valore di questo lavoro?

Do lo stesso valore che aveva cinque anni fa o dieci anni fa, anche se il lavoro in se è cambiato perché il mercato è cambiato… anche i pericoli insiti nel fare questo lavoro sono cambiati… Trovo che – forse – da alcuni punti di vista, fosse più facile fare questo lavoro vent’anni fa più che adesso. Ad esempio: molti anni fa il pericolo relativo ai sequestri a scopo di estorsione era decisamente inferiore, il dilagare del fondamentalismo islamico non ha aiutato questa professione, l’ha resa più “volatile”, più pericolosa, più difficile… però la tecnologia l’ha resa anche più accessibile, anche a giovani fotografi che vent’anni fa non sarebbero andati in determinati posti.

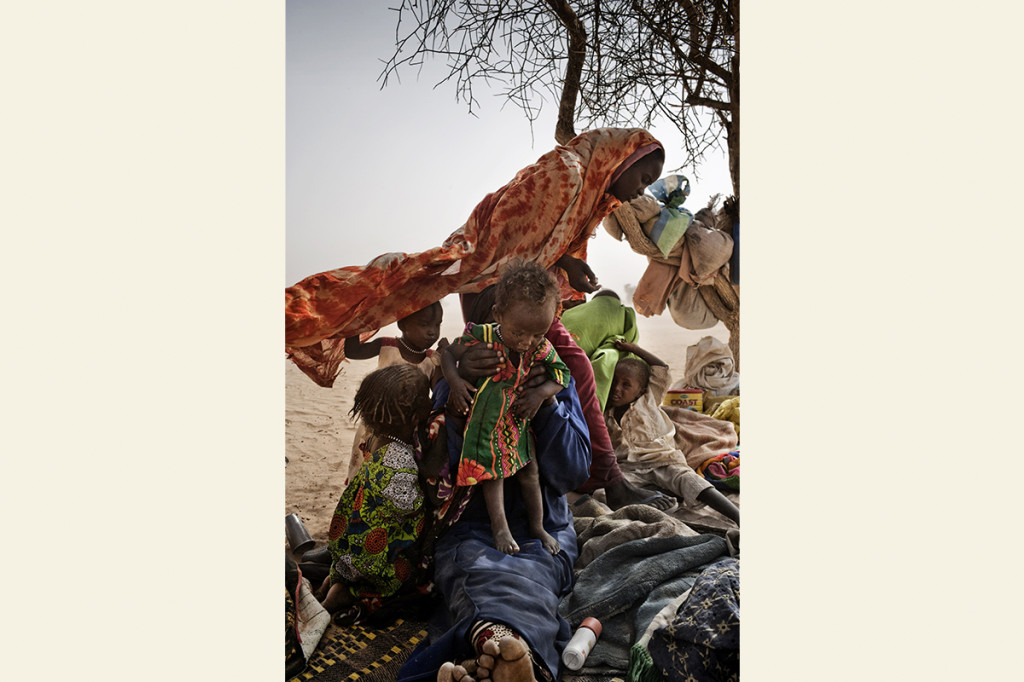

Fotografare la guerra porta inevitabilmente a confrontarsi con la morte e il dolore. Nelle tue fotografie non ti sottrai, e scegli di guardare l'una e l’altro. Non solo e non sempre. In alcuni tuoi lavori, ad esempio in July War e The Aftermath of Saddam, ci sono diverse immagini esplicative da questo punto di vista. Che importanza ha per te fotografare questi due momenti della vita di un individuo, e soprattutto poi restituirli al pubblico in immagini?

È molto importante, perché fa parte della missione del mio lavoro, di informare l’opinione pubblica riguardo alla condizione umana… non mi sottraggo al dolore delle persone che fotografo, provando a mia volta dolore per la loro sofferenza, tant’è che ho sempre la necessità di fotografare molto vicino. La maggior parte delle mie fotografie è presa da una distanza ravvicinata, con una lente 35mm, quindi non c’è mai una distanza tra me e il soggetto, per la natura del mio lavoro mi capita di passare mesi con questi soggetti.

Emerge quindi anche la responsabilità del reporter, quella di restituire l’intimità di questi soggetti?

Certamente. È una responsabilità grande, ma che ha un suo limite: quello di essere una sola persona, che documenta una storia, che può avere molteplici aspetti… è sempre una verità parziale, la mia verità, quella che è filtrata dalle mie opinioni, dalle mie idee, per quanto io cerchi essere neutrale o imparziale, posso essere comunque in un solo posto alla volta.

Voi fotografi siete comunque consapevoli che le vostre immagini andranno poi dentro ad un meccanismo editoriale: vi interrogate sul fatto che le vostre immagini vanno a finire in un processo più articolato?

Rifletto su questo tipo di responsabilità ma, lavorando per una grossa struttura come Getty che mette online le foto a disposizione di migliaia di clienti, la responsabilità ricade anche sul cliente, cioè usarle nel modo corretto. A volte succede che non vengano usate nel modo corretto, che vengano storpiate o riscritte le didascalie, che vengano inserite in un contesto non appropriato… addirittura vengono copiate e usate come propaganda, come è successo con una mia immagine abbastanza famosa che ho fatto in Iraq, usata dieci anni dopo come propaganda per la guerra in Siria.

Non è quindi un lavoro che fai da solo. Da solo fai la fase della ripresa, ma poi l’utilizzo dell’immagine è talmente vasto e vario, che non hai più nessun controllo.

Con alle spalle una carriera di quasi vent’anni, tu hai già visto mutare questo mestiere… ce ne vuoi parlare?

L’ho visto mutare soprattutto negli ultimi cinque anni, verso una direzione che io chiamo il “fast food dell’immagine”. Le buone fotografie, le grandi fotografie, non si fanno più su assignment di un giornale – in quanto ormai gli assignment si sono ormai ristretti ad una media di tre giorni – ma si fanno lavorando a progetti personali. Se un giornale mi chiama per fotografare la condizione dei minori migranti in Sicilia, e mi da tre giorni per farlo, è ovvio che difficilmente potrò mai tirar fuori un lavoro particolarmente degno di nota. Anni fa erano di una settimana, adesso son diventati di tre giorni… il lavoro di approfondimento lo puoi fare se fai progetti personali, a lungo termine, altrimenti se fai il fotografo di news, come per Getty News, AP, Reuters, quando accade un avvenimento specifico, come a Gaza o in Iraq, l’agenzia a volte ti permette di rimanere dei mesi per documentare sul campo.

Fino al 2007 ho fatto il fotografo di news per Getty Images, quindi fornivo una documentazione quotidiana degli eventi che mi dicevano di coprire o che sceglievo di coprire. Dal 2007 ad oggi questi assignment per i clienti dell’agenzia, si sono ristretti da sette, a cinque, e poi a tre giorni di durata. Prima riuscivo a gestire dieci assignment da 10-15 giorni ognuno in un anno, adesso ne faccio 40 di tre giorni ciascuno. Economicamente non è cambiato molto, ma è cambiata la qualità delle immagini che si producono.

A questo proposito, tu hai una grande attenzione per la qualità dell’immagine, per la composizione, la luce. E' una condizione che ti imponi, quasi un dovere? Quanto è importante per un fotografo, relativamente a questo contesto?

È una cosa che dipende dalla mia formazione culturale, dal mio background artistico, dagli studi che ho fatto, dagli studi che faccio sulla luce e sulla composizione, dall’attenzione e dai sacrifici che compio per riuscire a realizzare delle immagini del genere, e dalla fortuna se vuoi, di avere a disposizione tantissimo tempo quando documentavo eventi a lungo termine. Se guardi la gallery di The Aftermath of Saddam trovi 25 immagini, ma quelle immagini sono state scattate nell’arco di tre anni, durante la mia copertura della guerra per Getty Images: ebbene, io in quei tre anni ho mandato in rete quasi 21.000 immagini. È chiaro che ho scelto le immagini che io ritenevo rappresentative di quei tre anni.

Questa ricerca c’è solo quando hai tempo, non può esserci quando hai un tempo molto più breve. Nonostante ci sia sempre una certa attenzione ed una ricerca, devi fare comunque informazione.

Come mi disse una volta Giovanni Gastel, uno dei miei docenti allo IED, «il fotografo è il risultato del suo background socio-culturale» e credo che sia vero. Più uno nutre il suo background culturale, più questo fa bene alla sua fotografia.

In The space center riprendi alcuni elementi compositivi poco presenti in altri reportage, tipici invece della fotografia documentaria: la centralità del soggetto, le simmetrie, l’uso di un’ottica normale. È il soggetto che si impone per sue caratteristiche e dunque lo restituisci visivamente o è una scelta tua di utilizzare questo stile?

Innanzitutto non avevo mai fotografato in un ambito di quel tipo. Fotografare all’interno di un centro spaziale è sicuramente diverso che fotografare un teatro di guerra, in Iraq o in Libano… inoltre, era un assignement in cui io avevo soltanto quattro giorni a disposizione, per un giornale americano che parla di tecnologia, non di news, quindi ho cercato di dare un taglio che soddisfacesse anche le esigenze del cliente. Dobbiamo tenere conto che ci sono mille tipi di fotografia diversa, e che alla fine, nonostante possiamo anche considerarci degli “artisti”, alla fine hai un committente che ti sta pagando per fare un lavoro, e devi soddisfare le esigenze del cliente, ed avere una visione simile a quella che il cliente ha in mente. Non sempre fotografi come vorresti o come potresti.

Crediamo che durante certi reportage sia difficile non coinvolgersi, non sentire l’emozione, che sia paura o empatia. Quanto incide nel tuo lavoro la dimensione emotiva?

Conta tantissimo, probabilmente è il risultato finale di quella che è l’immagine. Se non provassi delle emozioni forti, non riuscirei a trasmettere con le immagini quella sensibilità o quella vicinanza. Come dicevo prima, ho bisogno di sentire - in un certo modo – quello che sentono i soggetti che fotografo. Con l’enorme differenza di potermene andare, mentre loro rimarranno poi in quella condizione… le emozioni più forti le provo durante il processo di editing, e al ritorno dagli assignment. Nel momento in cui scatto, nelle situazioni più concitate o di grande pericolo, devo cercare di mantenere una sorta di filtro – non un distacco, perché non riuscirei – dai soggetti che fotografo, che mi faccia sopravvivere e non mi faccia crollare emotivamente.

Posso però dire che i momenti più dolorosi della mia vita sono stati al momento del ritorno a casa… durante il processo di editing devi convivere con il dolore che hai assorbito durante il lavoro… con i fantasmi che questo genera, e con gli incubi che questi provocano… Sono dolori che ti porti dietro per tutta la vita… forse si “calcificano” nel tempo, ma una sorta di dolore ti rimane sempre, negli occhi o nell’anima, in qualche modo. È indiscutibile che vedere gente che muore per 20 anni consecutivi non faccia bene, nessuno ne è immune.

Adesso che ho ridotto l’esposizione a questo tipo di eventi, soffro meno. Ora che alterno diversi tipi di lavori, ho una vita più serena.

Vent’anni di questo lavoro hanno profondamente condizionato la tua vita quindi...

Mi hanno certamente condizionato, fino a quando non ho scelto di alternare diversi tipi di lavoro: adesso faccio di tutto, da lavori commerciali a lavori corporate, tutti i generi possibili che si fanno per un’agenzia come Getty Images.

Cosa vuol dire, per te, raccontare con la fotografia? E come ti rapporti con la costruzione di un racconto?

Per me la narrazione è semplicemente l’evolversi degli eventi. Nel momento in cui seguo una storia, il racconto non ce l’ho in testa fin dall’inizio. Ne ho una vaga idea, ma poi il racconto va per singole immagini che non hanno niente a che vedere con una cronologia, ma semplicemente con quelle che sono le mie emozioni. La singola immagine ha ovviamente la capacità di raccontare, ma ovviamente quando vedo un reportage fotografico, mi piacerebbe vederlo nello stesso modo in cui leggo un libro, con un prologo, uno svolgimento, e tutto il resto… vorrei avere la stessa sensazione che ho quando ho finito di leggere un libro.

La maggior parte dei reportage che vedo, nonostante siano molto validi, secondo me hanno degli editing troppo lunghi. Alle mostre, o soprattutto ai festival, vedi reportage di 70 immagini… non c’è bisogno di un editing così vasto per farmi capire una storia… preferisco la sintesi. 25-30 immagini potrebbero essere sufficienti… è anche una cosa che impari, lo spettatore non lo devi annoiare. … Non puoi però neanche ammorbare chi guarda… sul sito ci sono circa diciotto storie, prova a immaginare se ogni storia avesse 50 o 60 immagini di questo tipo.

Nel reportage Internally Displaced c’è una foto di un giovane guerriero, ripreso dal basso, con la sigaretta in mano e lo sguardo in camera. Quella situazione, se ti ricordi, da dove nasceva? Cos’è, per te, quello sguardo? E' simile a molti altri sguardi che fotografi o ha qualcosa di specifico?

Credo fosse lo sguardo di uno che si chiedeva cosa io stessi facendo… tieni conto che quella è una persona con cui ho passato diverse giornate, perché era al seguito di un “commilitone” ferito che veniva portato da un posto all’altro, in questo flusso di rifugiati. Era una persona che si era forse anche abituata alla mia presenza. In alcuni casi, guardando un'immagine riesco a percepire se lo sguardo è quello di una persona che ti ha appena incontrato, o se è lo sguardo di qualcuno che ti conosce… A me non disturba che il soggetto guardi in camera… dipenda da cosa voglio trasmettere, dipende anche se poi in fase di editing la foto mi piace o meno… Conta che io scatto moltissimo, e il mio processo di editing è molto lungo, molto accurato, e non lo faccio da solo.

Ecco, vuoi dirci come funziona l’editing dei tuoi lavori?

Ho una managing editor di Getty Images a New york, Lauren Steel, con cui lavoro ormai da tantissimi anni. Una volta finito un reportage, mando a lei una prima bozza di editing, e ne discutiamo fino a quando non arriviamo – di comune accordo – ad un editing finale. È la fortuna di avere alle spalle una struttura molto efficiente… Poi è anche una questione individuale: ci sono fotografi che l’editing lo fanno da soli, e basta. Per me è una scelta, mi piace avere un confronto… la fotografia è confronto continuo: per fare un esempio, uno degli ultimi editing di cui non ero soddisfatto, l’ho fatto fare a Paolo Marchetti [che ha indicato Di Lauro come suo passaggio di “testimone”, NdR]… non ho nessun problema a confrontarmi anche per l’editing con diverse persone. E un occhio esterno non è influenzato dall’emozione che tu hai provato nel fare quella foto.

Nel tuo sito alla sezione portfolio c’è una sottosezione Hipstamatic. Sono tuoi personali esperimenti o è parte di un approccio alla fotografia realizzata con smartphone e cosa ne pensi dell’uso che se ne fa a livello professionale?

Non è una ricerca, non voleva avere nessuna velleità particolare… semplicemente, nella vita quotidiana non giro con una macchina fotografica, a differenza di altri fotografi che lo fanno: giro semplicemente con un iPhone, e fotografo quello che mi incuriosice, o mi appassiona, mi diverte, o mi circonda.

Passo tantissimo tempo nella natura, perché sono appassionato di vari sport all’aria aperta, e spesso e volentieri fotografo usando questa applicazione. Un giorno, per gioco, ho messo insieme tutte le foto fatte con Hipstamatic, ho fatto un editing, l’ho mandato al mio editor a NY e le ho chiesto se mi aiutava a fare una serie che potessi mettere sul sito come un divertissement… e li è rimasto! È un gioco. Anche se poi ci sono fotografi di grande levatura che hanno usato quelle applicazioni per fare lavori che poi hanno vinto il WPP, come Ben Lowy per esempio. Per me è semplicemente un gioco, per altri è una ricerca, una cosa seria.

Rispetto all’interazione con il multimediale come ti stai comportando? Lo ritieni un ambito di sviluppo per la tua professione?

Ritengo la dimensione del multimediale fondamentale e interessantissima. Trovo che oggigiorno nessun fotografo possa esimersi dalla capacità di poter fare dei video. Io ho un grosso cliente, per il quale lavoro abitualmente, per il quale faccio anche dei video. Devo ammettere però, che mi trovo più a mio agio con la semplicità dell’immagine piuttosto che con il movimento del video. Se avessi voluto fare l’operatore o il videografo avrei fatto quello anziché fare il fotografo. La tecnologia oggi è cambiata, le esigenze dei giornali sono cambiate: sicuramente se uno ha la possibilità di fare dei video ha molte più possibilità di lavoro rispetto a chi fa solo fotografie. Trovo che l’insieme di testo, immagini e video se messi insieme in un certo modo, possano creare un prodotto meraviglioso, con un impatto molto più potente rispetto alla semplice fotografia e basta. Però richiede molto più tempo, richiede delle capacità diverse, richiede un lavoro di team.

Fai parte dell’agenzia Getty che recentemente ha cambiato il rapporto con l’utilizzo delle fotografie in rete. Cosa cambia per voi professionisti? Il giornalismo è mutato?

Sicuramente l’utilizzo di tecnologie diverse è parte di questo cambiamento. Il grosso cambiamento sta anche in quello che è il nuovo business, cioè da quando l’editoria è in crsi e ci sono meno fondi, si cercano fondi in altri ambiti. Il cambiamento è anche questo: la diversificazione del business vero e proprio.

Hai dei progetti personali che stai portando avanti?

Al momento no, sto cercando di entrare in quella che chiamo la “terza fase” della mia vita e della mia carriera: la prima fase era quella di fare il fotografo di news, dall’inizio della mia carriera fino al 2007, la seconda fase è stata quella dal 2007 fino ad oggi, cioè fare il fotografo su assignment commissionati dall’agenzia per i clienti dell’agenzia, da ora in avanti vorrei cercare di fare dei progetti personali che mi interessano, a lungo termine. Credo di aver ormai raggiunto la maturità professionale, e la solidità finanziaria per poterlo fare. Ho un paio di idee su cose che mi piacerebbe fare, che però non vi racconto...

Cosa vuoi restituirci con la fotografia? Dove va il tuo sguardo?

Il mio sguardo va alla gente che ne ha bisogno: bisogno di raccontare le proprie storie, bisogno di avere una voce che venga elevata all’attenzione dell’opinione pubblica… non mi interessa la fotografia in quanto tale: onestamente, che io faccia il fotografo è un puro caso, forse dato dal talento, dalle possibilità che ho avuto, dalle influenze che ho avuto… se avessi fatto il fotografo o lo scrittore, o il giornalista o lo scultore o il pittore, la mia attenzione sarebbe andata verso l’esigenza di raccontare problematiche sociali, o temi che hanno bisogno di essere raccontati, a mio avviso… non mi interesserebbe fare il fotografo di sport o di moda, mi interessa raccontare delle storie che hanno a che fare col sociale.

A chi passi il testimone?

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

Marco Di Lauro was born in Milan in 1970. Pushed by his mother, he starts practicing photography at a very early age. This passion grows stronger and stronger with time. After studying History of Art and Journalism, he graduates in Photography at IED, Milan. Since then, his career as photographer has been defined and developed greatly - from the first freelance reportages to collaborating with international agencies and magazines, often covering war zones, conflict and natural disasters.

He’s been part of Getty Images since 2002.

You are a reporter who operates in areas of conflict and humanitarian emergencies. We’d like to start from this experience of yours. First things first: why did you decide to be a reporter in these contexts?

I believe this choice is part of a personal path I started at 18 - I was working as a Red Cross paramedic in Milan, the city I lived in at the time. Perhaps that’s my first experience linked to social [affairs], and that’s when I realized I wanted to do a job that had a social function as well as paying the bills to get to the end of the month… Working as a paramedic has taught me a lot about people, the problems of the society I live in. As I enrolled into Literature and Philosophy with the idea of becoming an art critic I grew more and more passionate about the composition of images, light, painting… Photography was already a hobby my mum had passed on to me when I was a kid, and I was extremely curious about geopolitics and “the rest of the world”…

What are the meaning and the value of this job today, especially in consideration of the shifts in technology and the market? Has the value of this job been altered in some way?

I value it just as much as five or ten years ago, even though the job has changed because the market has changed - and so have the risks inherent to it. Perhaps I think that, considering certain points of view, this job was easier twenty years ago than it is now. Here’s an example: many years ago the danger of kidnapping and extortion was far lower, the spreading of Islamic fundamentalism hasn’t helped out my job - it rendered it more volatile, dangerous and difficult. However, technology has made it even more accessible, even to young photographers who wouldn’t have gone certain places some twenty years ago.

Photographing war inevitably leads to confront death and sorrow. In your photos you don’t back out, and you choose to face them both. That is, it’s not just that and it doesn’t happen at all times. In some of your works, see July War and The Aftermath of Saddam, there are a few images that express this point of view. What’s the importance to capture these two moments of a human being’s life - namely, to give them back to the audience as pictures?

It’s very important, because it’s part of our job’s mission, that is to inform public opinion about the human condition. I don’t back out from the sorrow of photographing my subjects - I do participate of their sorrow in turn, so much so that I always need to shoot from a very close distance. Most of my photos are shot from a very short distance, with a 35mm lens, so that there is never really much distance between me and the subject. Plus, considering the nature of my job, It happens to spend months with these people…

So the reporter’s responsibility emerges, too… That is, giving back the intimacy of these subjects…

It’s extremely important indeed. It’s a big responsibility, but it has its limits: that is being just a single person, documenting a story that may feature several aspects. My truth is always a partial one - it’s filtered by my own opinions and ideas. It doesn’t matter how much I try to be neutral and impartial - I can only be in one place at the time.

You photographers are still aware of the fact that your pictures will end up into an editorial mechanism. Do you wonder about the fact that your photos will enter this articulated process?

I do ponder upon this kind of responsibility, as I work for such a big establishment as Getty - they put online photos that are on display for thousands of clients. Responsibility lays on clients, too, in that they should be used in an appropriate manner - and sometimes it does happen that they won’t be used appropriately. They will be twisted or placed in a wrong context, or the captions [will] be rewritten. They will be even copied and exploited as propaganda, as it happened with one of my photos that I took in Iraq - it got utilized ten years later as propaganda for the Syrian war…

Therefore it’s not a job that you carry on by yourself. Shooting is the phase you do on your own, but the use of the images is so vast and varied that you just won’t have any kind of control whatsoever.

With a career spanning over twenty years, you have seen this job change…

I’ve seen it change mostly in the past five years, towards what I like to call the “image fast food” direction. You don’t take good, solid photos on assignment for magazines any longer - for their assignments have shrunk to an average of three days; rather, you carry them out working on personal projects. If a newspaper asks me to shoot the condition of underage migrants in Sicily and gives me three days to do it, it goes without saying that it’ll be quite unlikely to produce a standout result. Years ago [assignments] would be a week-long projects, which have now been reduced to three days. In-depth work can be carried out if you’re working on personal, long-term projects. Instead, if you’re a news photographer for, say, Getty News, AP, Reuters, when a specific event takes place like in Gaza or Iraq then the agency may allow you some seven months to spend on location and document the situation.

Up to 2007 I was a news photographers for Gerry Images, and as such I’d provide daily reports of the events I was told to cover or that I chose to cover myself. Since 2007, these assignments for the agency’s clients have shrunk to seven, five and then to three days. In the beginning I was able to manage ten assignments of ten-to-fifteen days each a year, whereas now I do forty three-day assignments…

Financially speaking, it hasn’t changed much - however, what’s really changed is the quality of images produced.

Speaking of which, you have a particularly attentive eye for image quality, composition, light… Is it something you force on yourself as a sort of duty…? How important is it for a photographer in connection to this context?

It depends on my cultural formation and artistic background, the studies I’ve done and keep doing on light and composition, the attention and sacrifices I make in producing such images, and - if you will - the luck of having so much time in my hands, when I used to make long-term reportages. If you look at the gallery of “The Aftermath of Saddam”, you’ll find twenty-five pictures, which have been shot over the span of three years as I was covering the war on behalf of Getty Images. Well, during those three years I put online almost 21k images. Obviously I chose the pictures I felt would best represent those three years. You can do this kind of research only when you’ve got enough time - it can’t be done when you have less time. Despite the presence of a certain care and research, you still have to provide information…

As I once told Giovanni Gastel, one of my professors at IED, «the photographer is the result of his socio-cultural background», and I believe it is true indeed. The more one feeds their cultural background, the more their photography will benefit from it.

In The space center you take some composition elements from other reportages, that are typical of documentary photography: the centrality of the subject and symmetries, and the use of normal lenses… Is it the subject that stands out for his own characteristics so that you give him back visually or is it your choice to utilize this style?

First of all, I had never shot in such a context. Shooting from within a space center is undoubtedly different to shooting from a war area in Iraq or Lebanon… Morever, it was a four-day assignment for an American magazine of technologies (and not a news magazine), hence I tried to shape it in a way that would prove satisfactory to the client’s needs. We must bear in mind that there’s a thousand of different styles of photography, and in the end, even though we might consider ourselves as “artists”, you still have a client who’s paying you to get a job done. And you have to satisfy his needs, whilst keeping a similar vision to the one the client has in mind. You don’t always get to shoot the way you wanted or could.

We believe that during certain reportages it’s difficult not getting involved and not feeling the emotion - be it fear or empathy. To what extent does the emotional dimension affect your work?

It counts a great deal, and it’s probably the final outcome of what the image is. If I didn’t feel strong emotions, I wouldn’t manage to convey that sensibility and nearness through pictures. As I was saying before, I need to feel - in a certain way - what the subjects I shoot feel. The massive difference is that I can get away from that condition, whereas they will be left with it anyway. I feel the strongest emotions during the editing process and when I return from an assignment. As I shoot in the most disturbed or dangerous situations, I must try to maintain some sort of filter (not a detachment, because I wouldn’t be able to) from the subjects I shoot - [a kind of filter] that will make me survive and not crumble emotionally.

However, I’ll say that the most painful times of my life have been at my returning home… Throughout the editing process you have to live with the sorrow you’ve absorbed during the job, the ghosts it generates and the nightmares they set free… These kinds of sorrow, you take them with you your whole life… They may “calcify” over time, but you’ll always endure a certain degree of pain - in your eyes or in your soul, one way or another. It goes without saying that to see people die for twenty consecutive years doesn’t do you good. Nobody is immune… Now that I’ve cut back on facing this sort of events, I suffer less… Now that I alternate different kinds of job, I’m leading a more serene life.

Twenty years into this job have influenced your life deeply…

They surely have influenced me until I decided to alternate different types of jobs. Now I do it all, from commercial to corporate assignments - all the possible genres you can do for an agency such as Getty Images.

What does it mean to you to tell a story though photography? How do you relate to the composition of a story?

To me, narration is simply the unfolding of events. As I follow a story, I don’t have its narration in my mind from the start. I do have a vague idea of it, but the narration itself evolves through single images which have nothing to do with a chronological order - rather, they deal with my emotions. Obviously each single image is capable of narrating, but when I see a photo-report I’d like to see it the same way I read a book, with a prologue, a plot and all the rest… I’d like to feel the way I feel when I finish reading a book.

Despite being extremely solid, I think most of the reportages I see have a much too long editing. At exhibitions and especially at festivals, I see reportages of seventy photographs… There’s no need for such a vast editing in order to make me understand a story. I prefer brevity. Some twenty-five / thirty images would suffice… It’s something you learn, too: the viewer mustn’t get bored… On the other hand, you shouldn’t overload the viewer either. On my website there are roughly eighteen stories… Try to imagine if each story comprised fifty or sixty photos of this kind…

In the Internally Displaced reportage there’s a photo of a young warrior shot from below, a cigarette in his hand and his eyes straight to camera. Do you recall where that situation originated from? What’s that look for you? Does it resemble other gazes you capture or something specific?

I think it was the look of someone wondering what I was doing… Keep in mind that I spent several days with that person, because he was wounded and following a comrade from one place to the next in this flow of refugees. He probably had got accustomed to my presence. In certain cases, by looking at an image, I manage to perceive whether the gaze belongs to a person who’s just met you, or to someone who knows you already… I don’t feel disturbed by the fact my subject looks into the camera… It depends on what I want to convey, and it depends on whether I like the photo or not during editing… Keep in mind this: I shoot a lot, and my editing process is quite long and accurate, and I don’t do it alone.

There it is… Could you tell us how your editing works?

I have a managing picture editor from Getty Images in New York, Lauren Steel, with whom I’ve been working for many years. Once I’ve finished a reportage, I send her a first editing draft, and we talk it out will we reach an agreed final editing. It’s the luck of being backed up by a very efficient structure. It’s also an individual matter: some photographers do their editing on their own and that’s it. For me, it’s a choice: I like having a confrontation. Photography is a continuous confrontation indeed… For example: I wasn’t satisfied with one of my last editings, so I had Paolo Marchetti do it [who indicated Di Lauro on his passing of the baton]… I’m perfectly okay confronting with different people for editing. In addition, an external eye is not biased by the emotion you’ve felt whilst shooting that particular photo…

Under your website’s portfolio category there is a subsection, Hipstamatic. Are these personal experiments of yours or are they part of an approach to photography through smartphones? What do you think of their use on a professional level?

It’s not a research, and it didn’t express any particular aspiration… Quite simply, unlike other photographers, I don’t stroll around with a camera during my everyday life: I’ll just have my iPhone with me, and I’ll shot whatever captures my curiosity, thrills and amuses me, or surrounds me.

I spend plenty of time in nature, because I’ve a passion for various outdoor sports, and I often shoot using this app. One day I collected all the Hipstamatic photos just for fun, I did an editing and sent it to my editor in NY, asking her to help me create a series I could upload to my website as a divertissement… And it stay there! It’s a game. However, there are renowned photographers who use these apps to shoot works that end up winning the WPP - see Ben Lowy. To me, it’s simply a game. To others, it’s a research… Something serious.

How are you interacting with multimedia? Do you consider it a field of development for your profession?

I deem the multimedia dimension particularly fundamental and captivating. I think nowadays no photographer is really exempt from the skill of making videos. I have a big client I work for on a regular basis for whom I create videos. However, I must admit I feel much more comfortable with the simplicity of an image rather than the motion of a video. Had I wanted to be a video-maker, I’d have done that instead of being a photographer. Technology has changed, the needs of magazines have changed. Obviously, if you have the possibility to make videos, you’ll get many more job opportunities compared to those who only takes photos. I think that the merging of text, images and videos, if put together in a certain way, can create a marvelous product, with a much higher impact that a mere photograph. It takes much longer, though. It requires having different skills and a team-work.

You’re part of the Getty agency, which has recently changed its relationship with online images. What changes for you, the professionals? Has journalism changed?

The use of different technologies has surely been part of this change. However, the big change lies in the new business, too. Namely, ever since the editorial industry faced its crisis and funds decreased, you look for funds in different contexts. This is change, too: the diversification of business itself…

Are there any personal projects you’re working on?

Not at the moment, no. I’m trying to head towards what I call “the third phase” of my life and career: the first phase was being a news photographer (from the start of my career until 2007), the second phase was between 2007 and now, i.e. working on assignments from an agency for clients of the agency. From now on, I’d like to try and produce personal projects that interest me, on the long run. I think I’ve reached my professional maturity, and the financial solidity to do it. I’ve a couple of ideas on things I’d like to do, but I won’t tell you…

What do you want to give us back through photography? Where does your gaze look at?

My gaze goes out to people who need it. The need of telling stories. The need of having a voice that gets raised to the attention of the public opinion. I’m not interested in photography per sé: honestly, the fact I’m a photographer is a pure chance - maybe it’s because of my talent, the possibilities I’ve had, the influences I’ve lived… Had I been a photographer or writer, a journalist, a sculptor or a painter, my attention would have been channelled towards the need of telling about social problems, or themes that need to be told. I wouldn’t like being a sports or a fashion photographer. I’m interested in telling stories that deal with social issues.

Who do you pass the baton to?

To Martina Cirese.

Leave a Reply