Lorenzo Castore, fiorentino di nascita e romano di adozione, si trasferisce a New York dove inizia la sua attività. Di ritorno a Roma si laurea in legge e inizia a fotografare in contesti e luoghi molto diversi. E' in particolare dopo un viaggio in India e dopo la visione di Exiles di Koudelka che si trasforma il suo modo di concepire la fotografia.

In questa intervista abbiamo cercato di esplorare la sua visione, caratterizzata da un personalissimo approccio alle cose e alle situazioni che fotografa.

Partiamo dai ritratti. Scegli tu i soggetti dei tuoi ritratti o sono anche legati a lavori commissionati?

Ci sono ritratti e ritratti, quelli che scelgo e quelli commissionati. I ritratti commissionati per definizione sono richiesti da qualcun'altro. Non c'è niente di male ma hanno un'origine diversa da quelli che voglio fare io. Poi, a parte rarissime eccezioni, non mischio mai il 'mio' lavoro a quello commissionato. Non so perchè ma è sempre stato così. Non è un motivo ideologico ma molto personale e neanche troppo chiaro a me stesso, diciamo che mi sento più a mio agio così.

Come ti avvicini a loro, come costruisci il ritratto? Puoi raccontarcene uno?

I soggetti che mi interessano hanno una forza magnetica.

E' un'attrazione che cresce progressivamente e che nei casi più eclatanti diventa una specie di ossessione.

L'altro (il soggetto ritratto) determina il rapporto quanto lo faccio io, è una cosa a due e quindi sempre diversa e misteriosa: l'unica variabile fissa è un intuito che genera curiosità reciproca e rivela affinità nascoste. E' una specie di reazione chimica.

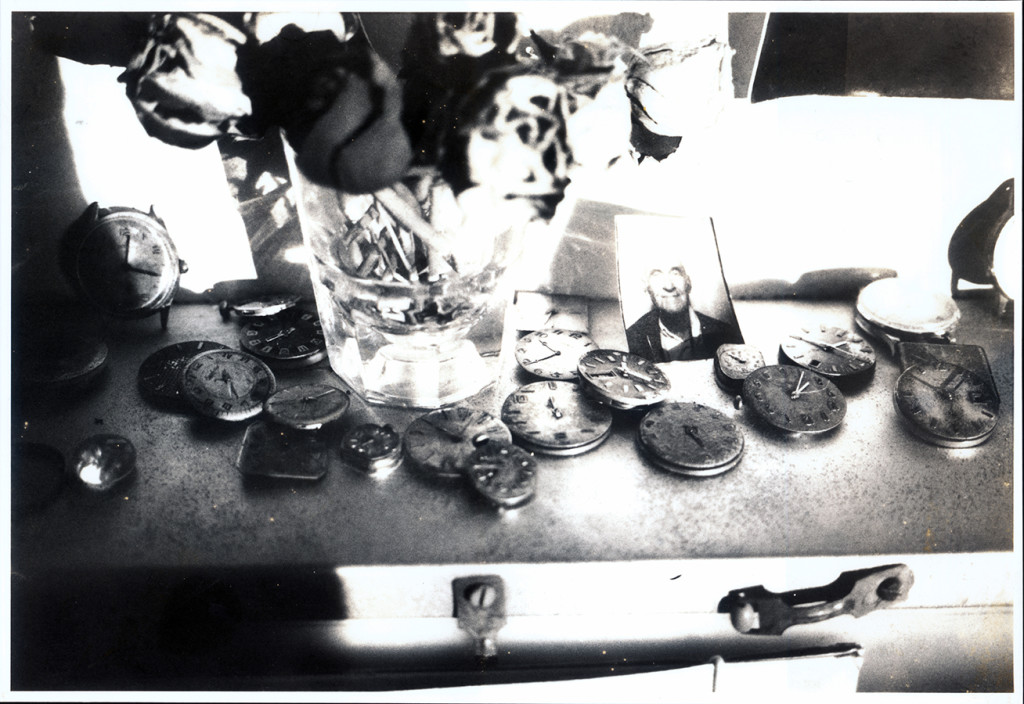

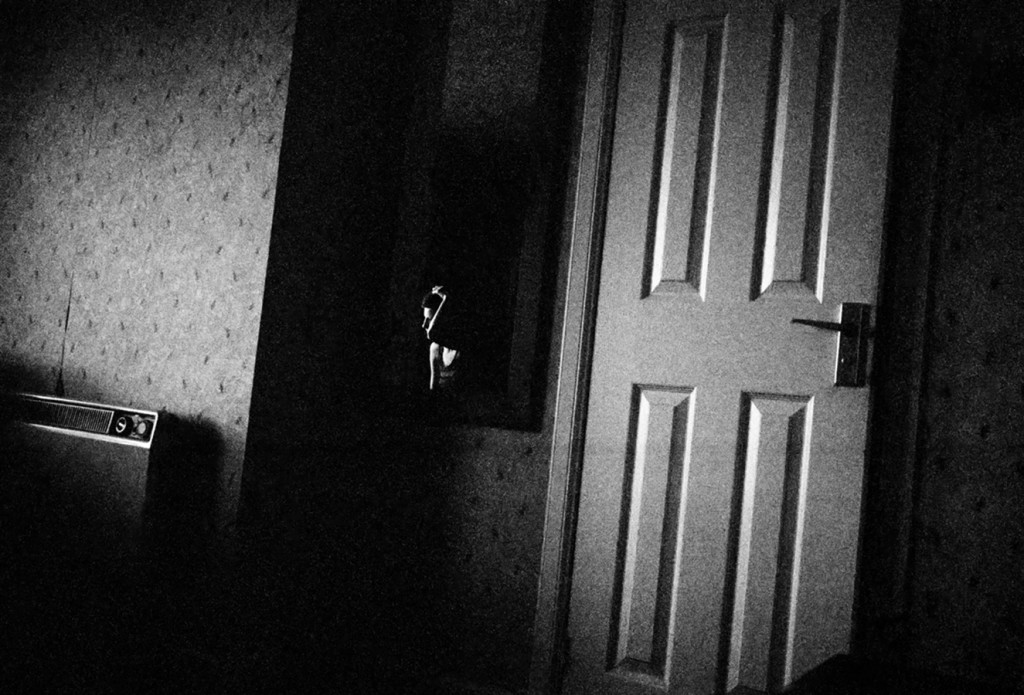

Posso raccontarti di Ewa e della prima volta che l'ho vista. E' stato su un tram. Non riuscivo a staccarle gli occhi di dosso. Mi faceva paura e mi attraeva, volevo avvicinarla ma mi sentivo goffo e insicuro nell'approccio e quando ho poi scoperto che abitava nella mia stessa strada non ho fatto altro che girarle intorno per due anni senza avere da lei il benchè minimo cenno di interesse. Quando mi avvicinavo mi respingeva con sprezzo, non ne voleva sapere nè di me nè delle mie fotografie. Poi tramite Ludmila, una mia cara amica da cui Ewa andava a vendere delle vecchie fotografie scattate dal padre, si è creato un contatto e poi si è stabilito un rapporto che è poi durato negli anni. Ho cominciato a fotografarla, ho conosciuto suo fratello Piotr, abbiamo passato tanto tempo insieme, ci siamo stati vicini fino alla fine. Ewa è morta lo scorso dicembre.

Credo che la cosa più importante nel ritratto sia l'energia che ci si mette, essere molto vicini e allo stesso tempo curarsi di mantenere una certa inevitabile distanza, anche se minima. Se ci si guarda allo specchio non possiamo farlo se ci stiamo appiccicati, non vedremmo più nulla.

La tua fotografia ci lascia una sensazione: sembra far parte degli avvenimenti nei quali ti trovi, come se le cose – umani compresi – ti si concedano per un attimo, perché tu appartieni a quel momento. Restituiscono la tua presenza nella scena. Come stai dentro una scena, come ti muovi?

Non lo so. Ci sono. Ci provo. Non penso a quello che dovrei fare, non penso alla fotografia ma cerco di fare in modo di svuotarmi. Essere lì dimenticandomi di me. Essere invisibile e presente insieme. Quando questo avviene nel modo più profondo, allora mi capita di perdere la cognizione del tempo. Avevo risposto a questa domanda in modo più approfondito ma poi ho cancellato quasi tutto perchè provo pudore per il tentativo di cercare di spiegare certe cose che sono così delicate ed impercettibili. Stare dentro una scena è il modo di manifestare la propria presenza ed è una sensazione fisica: io sono una persona molto fisica e per me la fotografia è una disciplina molto fisica.

Nelle tue fotografie troviamo diverse cose: la sospensione (qualcosa accadrà), il congelamento di un attimo che lo fa apparire unico, l’instabilità, l’evanescenza - come ad esempio in Ewa&Piotr - sono tutti elementi che caratterizzano molta tua fotografia. Sono dimensioni liminali, sottili. È cosi? È questo che ti interessa catturare?

Si, certo mi interessa tutto quello che dici. E tante altre cose. Soprattutto ciò che genera tensione, gli opposti che convivono e quello che non capisco e che non metto esattamente a fuoco. Appartenere a qualcosa che attrae e che respinge, cercare di avvicinarcisi. Sentirsi parte di qualcosa che è di tutti e allo stesso tempo soffrire di un intimo isolamento.

La vita è davvero una cosa meravigliosa non perchè è bella (quando lo è) ma perchè è un mistero dal quale - se ti va bene - inaspettatamente emergono lampi di rivelazione.

E' difficile parlare di queste cose proprio perchè sono sottili, si diventa subito aulici, si passa per presuntuosi o filosofi da quattro soldi e io preferirei evitarlo tanto la verità sta nelle azioni più che nelle parole.

Come scegli le tue storie?

Come i soggetti dei ritratti, è la stessa cosa.

Puoi raccontarci come prepari operativamente il tuo lavoro?

Non c'è un metodo. Almeno io non credo di averlo. Succede qualcosa e quando ha un impatto forte su di me cerco di seguire quel qualcosa e quell'impatto forte. Questo succede sempre, ma poi il come è sempre diverso. Sono convinto dell'importanza di mantenersi amatori, la specializzazione e il professionismo non fanno per me. Non mi piace sapere troppo cosa sto facendo, dopo molto poco mi annoia e allora perdo convinzione. Chiaramente sto parlando del mio lavoro più personale, non del commissionato che è un'altra cosa: ha a che vedere col mestiere e con un interlocutore che chiede un lavoro specifico. E in ogni caso ci sono fotografi che fanno le loro cose migliori su commissione e hanno un ferreo metodo di lavoro sempre uguale che gli fa fare cose bellissime.

Non ci sono regole assolute, ognuno ha le proprie e credo sia bene attenercisi quando le si sono trovate e funzionano per noi. Salvo poi cambiarle, se necessario.

I tuoi lavori fotografici sembrano far emergere in modo costante il tema dell’identità, dei luoghi e delle persone - e in alcuni casi il tema è dichiarato - pensiamo ad esempio a Ultimo domicilio, o in Sogno #5. E’ così?

L'identità, i luoghi e le persone sono il territorio comune di tutta l'umanità. L'identità è probabilmente il tema più altisonante dei tre da te indicati ma - anche se banale - è necessario sottolineare che l'identità non può esistere senza i luoghi e le persone. Le vite di ogni essere umano sono una tensione - giusta, sbagliata, fallita, riuscita, vuota, strutturata, conscia, inconscia, originale, omologata e così via - verso la ricerca della propria identità.

E' un tentativo che in un modo o nell'altro facciamo tutti, poi tra il dire e il fare c'è di mezzo il mare.

Faccio un paio di esempi in relazione ai due lavori che hai citato.

L'origine di 'Ultimo domicilio' risale al 2008. Sono stato a Sarajevo e a Mostar perchè ritornava in me il pensiero della mia prima esperienza da fotografo 'professionista' ovvero dei due mesi passati tra Albania e Kosovo nel 1999.

Quella è stata un'esperienza indimenticabile per l'intensità, la violenza e la rapidità con cui mi sono dovuto confrontare con quello che volevo provare a fare e il mondo vero. Appena tornato a casa mi ero ripromesso di non tornare più in zone calde dove succedevano fatti di importante rilevanza mediatica perchè in generale ero deluso dalla manipolazione delle notizie, dall'impossibilità di capire davvero cosa stava succedendo e poi perchè disgustato dall'atteggiamento adrenalinico e assetato di sangue di certo giornalismo.

Il disagio dipendeva anche dal fatto che la voglia di autoaffermazione era qualcosa che anche io conoscevo e da cui non volevo farmi sopraffare.

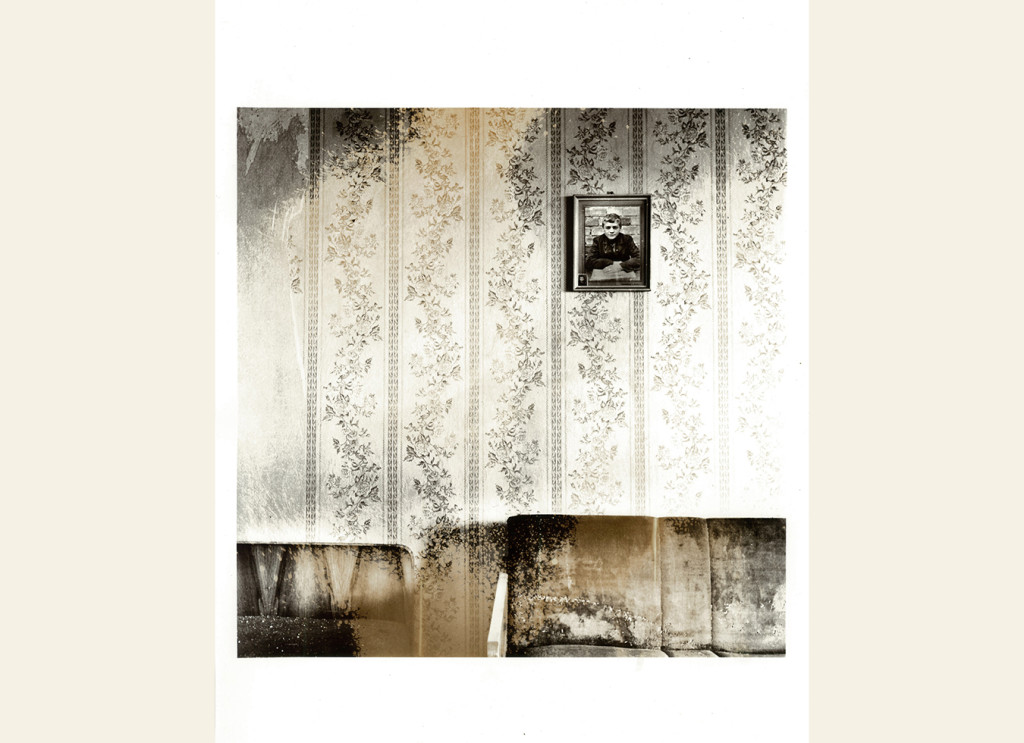

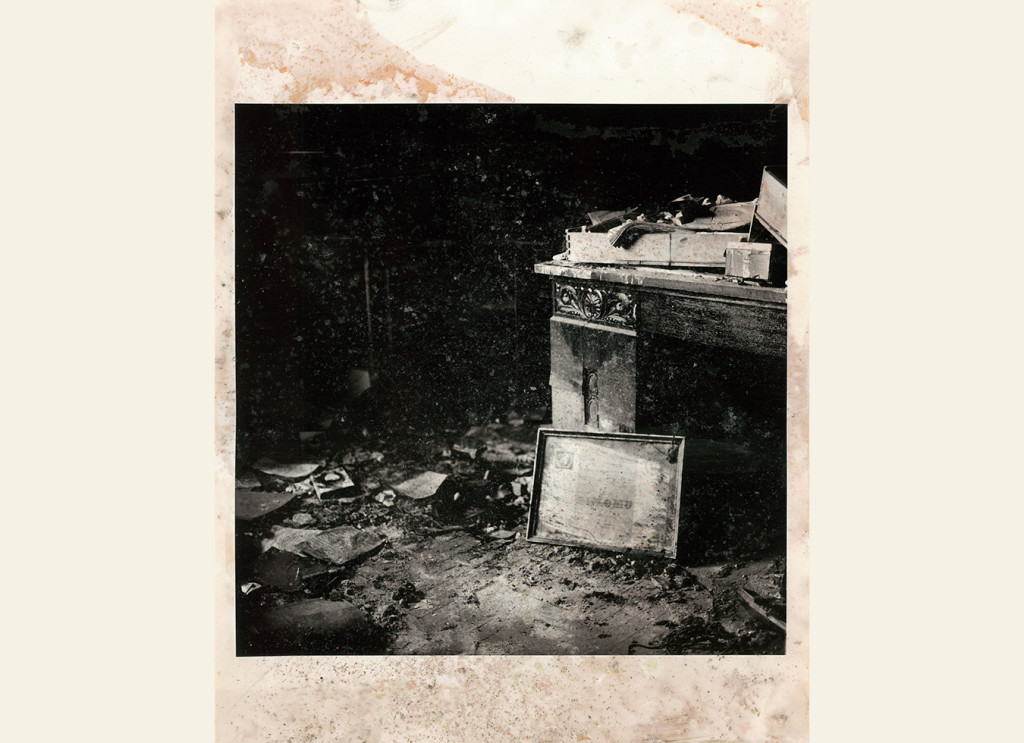

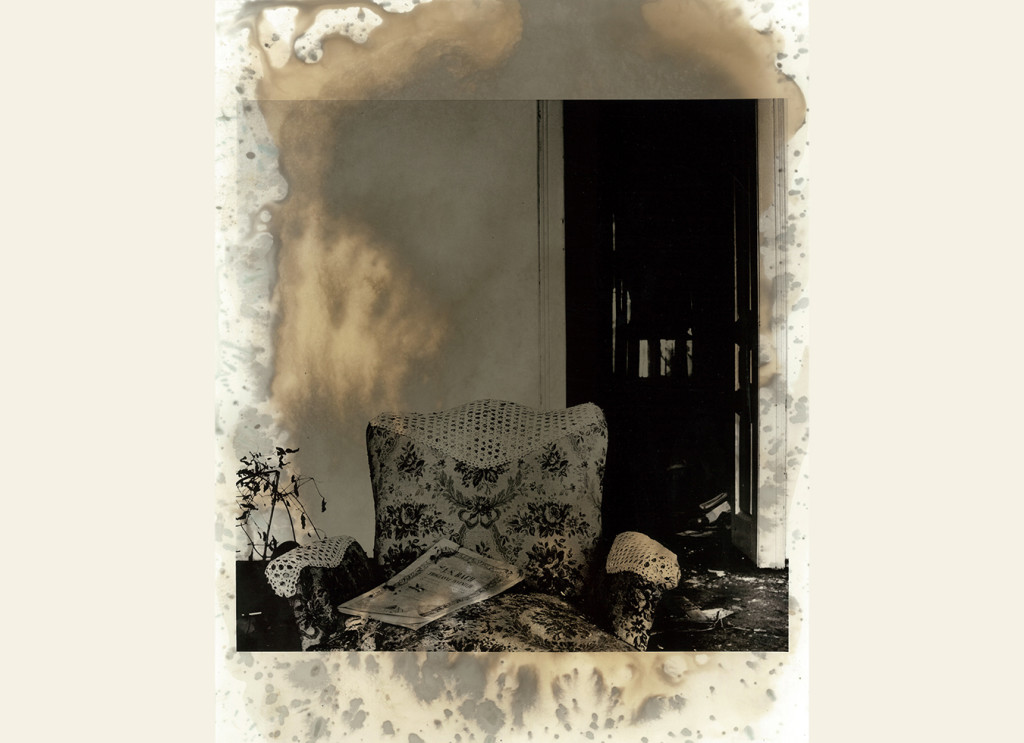

Così negli anni in me è cresciuto il desiderio di tornare da quelle parti (anche se poi sono andato a Sarajevo e a Mostar e non in Kosovo) a cercare case abbandonate durante la guerra e mai più riabitate. Case lasciate dietro di sè da un giorno all'altro insieme a tutti gli effetti personali che le identificava con chi ci viveva.

Non cercavo storie disperate ma case ancora almeno semi intatte o portatrici di una presenza e quindi di una storia. Erano passati 9 anni dal mio tempo lì e non è stato facile trovare quello che cercavo. La guerra e l'assedio avevano cambiato tante cose: famiglie avevano dovuto migrare e le loro case erano state distrutte, a volte ricostruite, altre per sempre abbandonate. Piccole storie insignificanti che non interessano a nessuno.

'Ultimo domicilio' però non era previsto, non ci stavo lavorando, avevo fatto un viaggio in Bosnia perchè volevo confrontarmi con quello che ho appena detto e niente di più.

Poi qualche mese dopo ero a casa mia a Cracovia e dopo aver steso la biancheria su uno stendino vicino a una stufa di ceramica sotto lo sguardo dritto di una coppia in una foto d'epoca presa al mercato delle pulci, allora in quel preciso momento tante cose hanno preso forma, si sono di colpo create associazioni, qualcosa si è rivelato e così ho deciso di cominciare a lavorare coscientemente a questo progetto.

L'anno seguente ho venduto quella casa e me ne sono andato da Cracovia. Quella è stata l'unica mia vera casa, o almeno quella che ho percepito come tale. Prima di lasciarla mi ci sono chiuso dentro due settimane, l'ho svuotata e fotografata tutta. Di guerre impercettibili è piena la vita di ognuno e certi universi costruiti con l'amore, con progettualità, conservando oggetti e ricordi che formano la nostra identità sono destinati ad essere lasciati indietro e scomparire. Lo dico senza nostalgia, così vanno le cose ed è giusto guardare avanti però è importante avere qualcosa di bello da ricordare.

Identità, luoghi, persone.

Per Sogno # 5 è tutto molto diverso ma anche simile e non lo racconto nel dettaglio perchè mi sono già dilungato troppo.

E' un lavoro che si interroga sulla malattia/sanità mentale, sul potere coercitivo delle istituzioni ma anche sulla biopolarità nelle relazioni e sulla fuga. O almeno questo significa per me.

Quello che voglio dire è che certo si parla di identità, di luoghi e di persone ma i passaggi per arrivare alle cose sono imperscrutabili, hanno molto a che vedere con l'attenzione: bisogna stare attenti ai segni che riceviamo dall'esterno e dall'interno più che essere intelligenti e/o furbi realizzatori di una bella idea non appena si crede di avere per le mani qualcosa che funziona.

E' la reale esperienza di un lavoro che lo rende speciale.

Spesso questi luoghi portano con sé la testimonianza di qualcosa che è successo, ad esempio, Sarajevo/Mostar (in Ultimo Domicilio) . Qual’è la ricerca o l’interesse che ti spinge in questi luoghi?

Credo di averti risposto a questo nella domanda precedente.

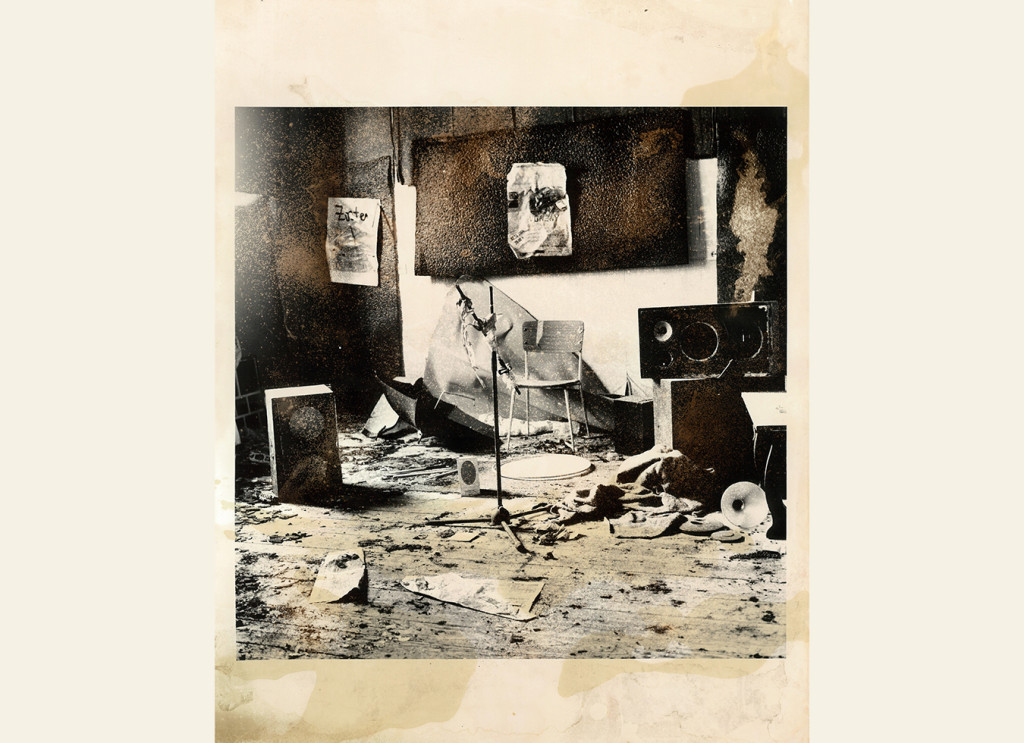

Posso aggiungere che ho cercato queste case per mesi dall'Italia senza produrre nessun risultato significativo. Poi mi hanno messo in contatto con una fondazione che aveva a che fare con il teatro della memoria di Sarajevo ma anche con loro niente. Sono andato e lì invece un amico di un amico, Nedim Zlatar, mi ha mostrato una casa che stava aiutando a far acquistare ad un suo amico francese, musicista come lui. Nei giorni seguenti mi ha portato a Mostar dove con altri ragazzi andavano in questo villino abbandonato a suonare: per qualche strano motivo la società dell'energia si era dimenticata di staccare l'elettricità e quindi loro ci andavano a provare gratis potendo attaccare strumenti ed amplificatori alla corrente, fino a che un giorno c'è stato un corto circuito, un principio di incendio e tutto il sistema elettrico è andato in malora. Cosa mi ha spinto ad andare in Bosnia a cercare quindi è stata una riflessione e un bisogno legato a qualcosa del passato, cosa mi ha poi davvero permesso di trovare quello che cercavo è stata la musica e una storia ricca di presente. L'esperienza è piena di sorprese.

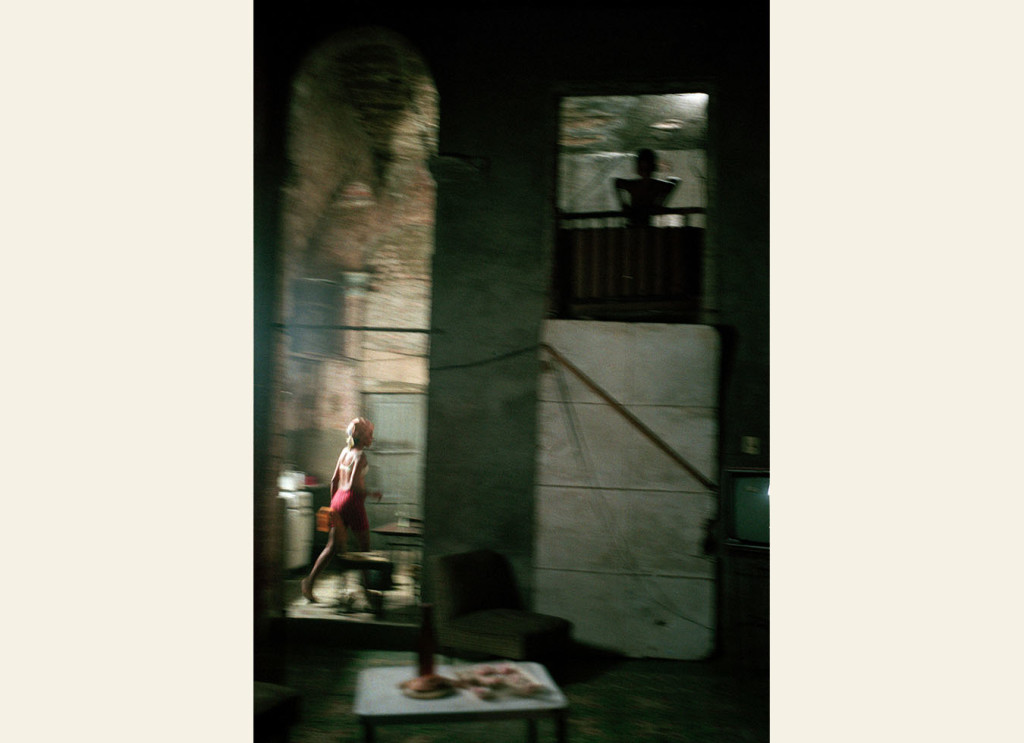

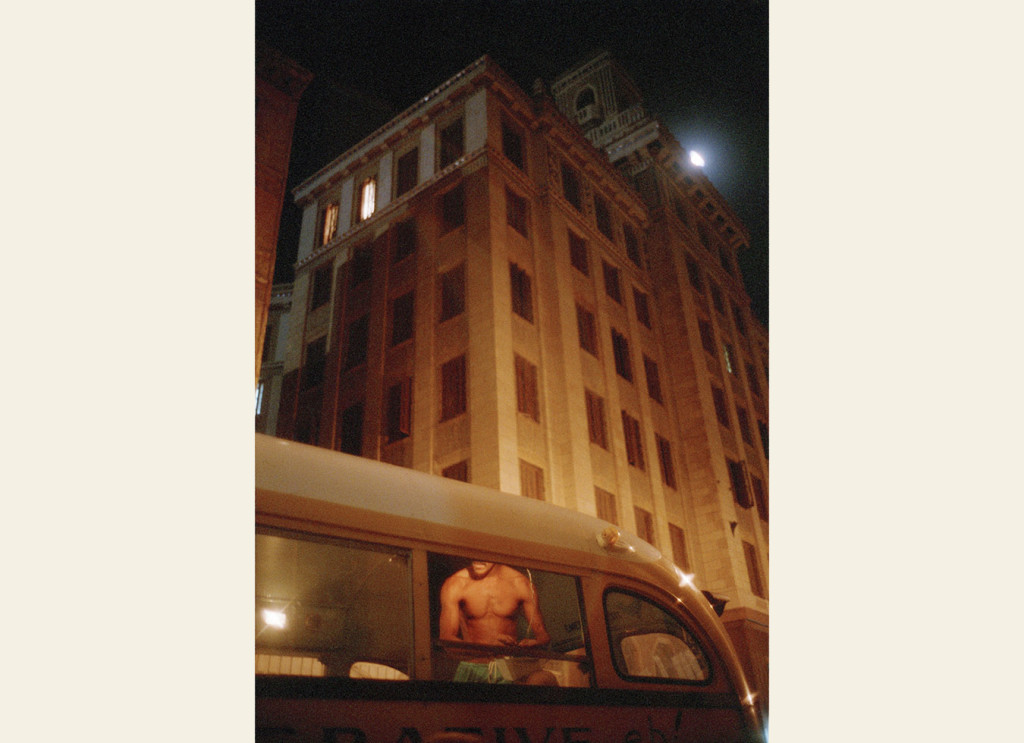

Spesso usi il mosso, lo sfocato, leggere asimmetrie, sottoesposizioni – che siano realizzate ad hoc o scelte successivamente poco importa – le scegli. Ad esempio in modo spinto lo troviamo nel tuo lavoro Paradiso/Avana, Cuba ma come in diversi altri lavori. Perché questo tipo di ripresa?

'Paradiso' credo che abbia un po' troppo influenzato la percezione del mio lavoro. Credo sia dipeso anche dal fatto che è stato il primo lavoro che ha avuto un certo successo.

In quel caso volevo fare fotografie a colori dove i colori non fossero decorativi o descrittivi ma davvero una parte attiva dell'immagine. E' davvero un lavoro sul colore, il colore che mi interessa. Mi sembrava di aver visto poche foto a colori che mi piacessero fino a quel momento. In seguito ho scoperto cose bellissime ma in quei giorni la fotografia a colori mi sembrava abbastanza inutile. E comunque avevo 28 anni e delle opinioni più nette e meno approfondite di oggi. Mi avevano descritto la luce dei lampioni di Havana e credo sia stato il motivo fondamentale per cui mi sono deciso a partire.

Volevo provare a fare una fotografia pittorica e quindi per avere certi colori e usare la luce di quei magnifici lampioni giravo tutta la notte e tutte le notti, e di notte con quella luce è inevitabile imbattersi in un certo mosso e andava benissimo così.

Una volta per provare l'effetto che fa ho provato a muovere la macchina mentre scattavo e mi sono sentito istantaneamente un vero cretino, ancora mi imbarazzo al pensiero di una tale idiozia. Da quel momento ho cercato sempre di tenere la macchina più ferma possibile anche se non ho rinunciato a fotografare a un quarto di secondo, se necessario.

Insomma voglio dire che lo stile per me è un problema un po' datato, sono molto più preoccupato dell'energia che metto e che torna indietro da quello che faccio.

Non credo di aver mai pensato di dover fare qualcosa per dover assomigliare al mio stile. Dal punto di vista del successo commerciale credo che questo mi abbia un po' danneggiato, soprattutto da dopo 'Paradiso' fino a tre-quattro anni fa, perchè il pubblico vuole sapere cosa va a vedere e chi fa cosa. Sapere di vedere quel fotografo o quell'altro dà certezze e rassicura, crea 'idoli' e questo alimenta tutto il baraccone. Oggi le cose vanno meglio perchè credo che il puzzle che ho cominciato a comporre 20 anni fa stia diventando più intellegibile anche per chi ama dividere il mondo in scatole e categorie.

Cerco di evitare tutte le cose che mi facciano sentire una caricatura. Non sono quello del mosso o dello sfuocato nè quello del colore o del bianco e nero nè quello della Holga o della Leica nè quello della Polonia o di chissà dove: ci sono tante cose insieme che ho fatto e che faccio, una alla volta, con tutta la cura e la unicità che ogni cosa che provo a fare merita per se stessa.

Ci puoi raccontare perché hai intrapreso il progetto Ewa&Piotr - No Peace Without War?

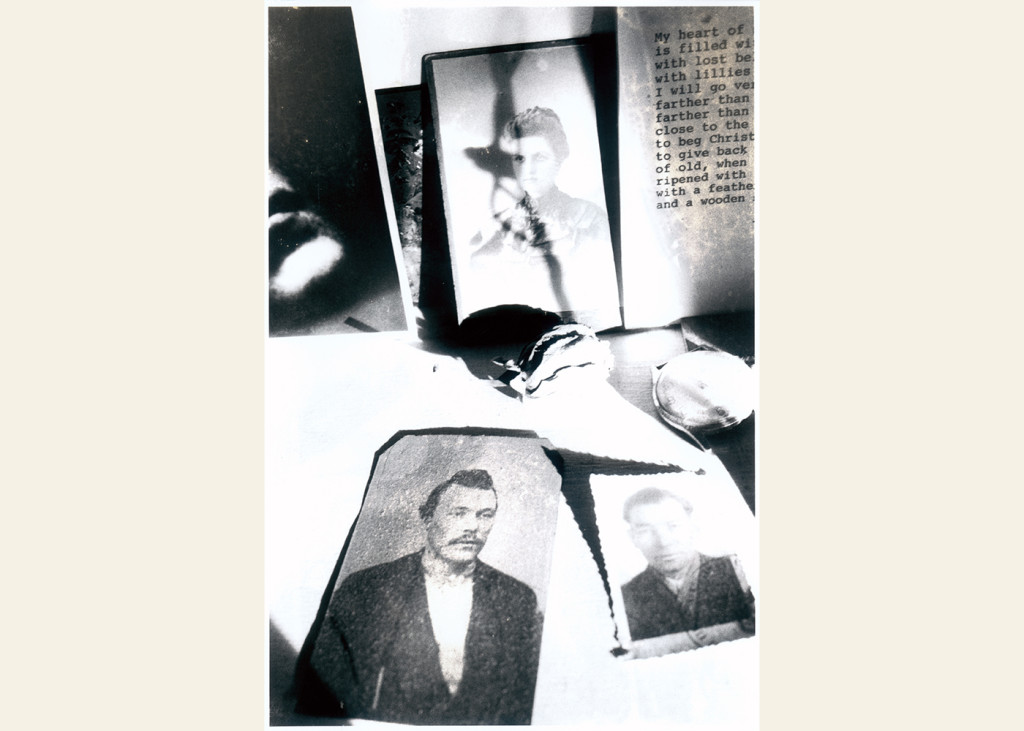

Ho incontrato Ewa che ha avuto su di me un impatto fortissimo. Poi, una volta finalmente presentati, mi ha invitato a casa dove ho conosciuto suo fratello Piotr. Abbiamo cominciato a frequentarci, a conoscerci, a volerci bene. Negli anni sono emerse fotografie del loro passato scattate principalmente da loro padre morto poco prima che tornassero a vivere insieme. Ti rispondo con delle righe che ho scritto quando mi sono fatto anche io questa domanda.

Perchè fare tutto questo?

Per il non-senso, per condividere un’esperienza umana, per non

giudicare, per la bellezza inaspettata, per il piacere di

identificarsi in tutto, per rendersi conto ancora una volta

che niente si fa da soli, per quello che non sappiamo e di cui

non si può dire.

La famiglia di Ewa e Piotr era una famiglia benestante, poi

hanno perso tutto. Tante sono le cause che hanno portato a

questo ma non voglio dire troppo di loro, non voglio

raccontare la loro vera storia con le mie parole o attraverso

la mia interpretazione razionale.

Ci sono le foto della loro infanzia, le mie del nostro tempo

insieme, e un film (co-diretto con Adam Cohen) che non

chiarisce niente, che non informa dei fatti, in cui Ewa e

Piotr parlano e dicono quello che vogliono dire e rispondono

come vogliono rispondere. Per reinventare, perche la verità

non è letterale ma assoluta e dappertutto. La storia di un

mondo in due stanze. Anche no. Una storia.

Ewa e Piotr sanno ridere e far ridere, hanno cultura, eleganza

e sensibilità. Non sono patetici. Sono quello che sono. Hanno

avuto quello che hanno avuto. La vita è una, e a volte è

strana. Piotr dice di no.

Utilizzi sia il bianco e nero sia il colore. Da cosa dipende la scelta dell'uno o dell'altro? E' legata a tematiche o situazioni specifiche?

Credo da entrambe le cose. Tendenzialmente faccio fotografie in bianco e nero però in casi specifici preferisco il colore.

Come ti relazioni con la narrazione?

Mi piacerebbe farlo meglio, innanzitutto. Poi è un tema molto aperto per me. In fotografia ha a che vedere con le mostre, con i libri, con le proiezioni e nell'immagine in movimento con il senso del montaggio, con il peso che si vuol dare alla parola e al suono. Sono tutti aspetti vicini ma che necessitano di punti di vista diversi per poi arrivare a fondere tutto in una cosa. E' importante essere chiari senza essere banali, comunicare senza troppo dire. Come farlo è ogni volta una epifania, o un aborto.

Utilizzi anche come mezzo espressivo il cinema. Cosa ti offre di diverso dalla fotografia e cosa invece trovi di simile? (ci teniamo a sottolineare che solo sulla tua produzione cinematografica sarebbe necessario fare un’intervista a sé, in particolare per il lavoro Eva&Piotr).

Per me il punto è come raccontare nel modo migliore ciò che ho bisogno di comunicare; la fotografia o il cinema sono dei mezzi, degli strumenti, non una religione. Se ne avessi avuto il talento avrei preferito la musica a tutto il resto. E' di gran lunga la mia arte preferita ma sono totalmente negato così negli anni ho cercato di indirizzare i miei presunti talenti nella direzione di quello che avevo voglia e bisogno di esprimere e condividere. Tutto parte da lì. Dello status di fotografo o chissà che cosa non me ne frega niente. Quindi mi sento libero di usare il linguaggio che mi pare più consono al contenuto di quello che voglio tirare fuori. E poi il cinema mi permette di usare insieme la parola, la musica e il suono. Mi piacerebbe continuare a fare film finchè avrò delle idee che mi sembrino meritevoli di tempo e attenzione, mia e altrui.

C'è un film che vorrei tanto fare ma per ragioni contingenti non ho più tanto tempo a disposizione. E' una specie di documentario dove è tutto pronto per essere girato ma purtroppo non ho fondi per continuare. Sono certo che potrebbe essere una cosa bellissima, impegnativa certo, ma per la quale sarei disposto a tutto. Invece ad oggi non lo posso fare e questo mi crea un profondo senso di frustrazione. Il cinema costa tanti soldi che anche quando non sono tanti sono tanti, e poi c'è bisogno di una struttura che gestisca il rapporto economico con l'industria cinematografica e questo - anche se su scala diversa e ridotta - vale anche, se non di più, per un cinema più anarchico ed indipendente.

Per tornare alla tua domanda: nel cinema si deve essere più precisi, si deve sapere con più chiarezza quello che si vuole fare anche se poi il film prenderà una forma inaspettata.

La fotografia è più ambigua. Poi nel cinema si lavora in gruppo e nella fotografia no. Il problema di base comunque è sempre lo stesso, si deve avere qualcosa da dire e trovare il modo che ci assomiglia di più per dirlo.

Sulla scia della domanda precedente, sappiamo che ami molto la musica e la pittura. Come ti influenzano, come fotografo? Che tipo di relazione stabiliscono con le tue immagini?

La musica è talmente presente nella mia vita che potrei rispondere a questa domanda solo attraverso il contrario ovvero quanto influenzerebbe la mia vita doverci rinunciare in maniera permanente e preferisco non pensarci. Per quanto riguarda la pittura ci sono dipinti che mi hanno colpito profondamente e che mi porto dietro negli anni, sono quelle immagini che ti si fissano nella memoria e ti si depositano dentro. Su di me lavorano come fanno anche certe immagini di libri o fatti realmente accaduti. Tutto si mischia e diventa la propria radice, una stella polare molto personale.

Il risultato pratico nelle mie foto credo stia nel fatto che cerco di ricreare continuamente certe immagini, consciamente o incosciamente, e non mi riferisco solo od esclusivamente al loro aspetto formale.

Hai qualche esperienza con i prodotti multimediali? cosa pensi di queste forme di interazione?

Non lo so, non sono un grande esperto di multimedia e di nuove tecnologie in generale. Ho un sito solo da un mese, non ho facebook nè twitter. Per il mio lavoro uso ancora la pellicola. Non ho niente contro le nuove tecnologie e i social network, anzi credo possano aiutare se usati propriamente però io non saprei come farlo.

Per quanto concerne più strettamente l'uso di tecniche ibride per la creazione di prodotti multimediali credo debba essere funzionale all'oggetto del racconto e non fumo negli occhi.

Che rapporto c’è tra il tuo approccio, per come lo conosciamo, e il mercato della fotografia? Che margini di libertà hai – o ti dai – quando ti trovi a realizzare un lavoro commissionato?

Cerco di avere più tempo possibile per lavorare a quello che mi sta a cuore. Per farlo devo guadagnare e cerco di farlo in ogni modo degno e possibilmente rapido così da avere più tempo e risorse da usare per le mie cose. Tutte le mie fonti di reddito sono saltuarie ed incostanti ma bene o male fino ad oggi ha sempre funzionato così.

Vendo per collezionismo ma non quanto vorrei, faccio workshop, a volte lavori corporate o pubblicitari e altre ritratti o mini storie per l'editoria, per anni ho avuto una certa regolarità con la documentazione dell'avanzamento lavori in grandi cantieri per importanti architetti e lo stesso ho fatto con le demolizioni di grandi opere, da pochi giorni mi sto occupando della riorganizzazione di Luz che è stata un'agenzia fotografica che stiamo provando a trasformare in una struttura più contemporanea e possibilmente innovativa. Te l'ho detto, la specializzazione non fa per me.

Cerco di essere elastico per adattarmi ai tempi e per avere più tempo possibile per quello che per me è importante.

C'è talmente tanto da fare per il lavoro personale che sul commissionato non vado a chiedere una libertà se non mi viene concessa e soprattutto se non saprei che farci. C'è un cliente che vuole qualcosa, quindi se accetto quello che chiede cerco di fare il lavoro nel modo migliore possibile. Altrimenti rifiuto il lavoro. Nessuno mi obbliga ad accettare. Non ho energia da sprecare per crociate contro cose che non mi interessano. Oltretutto nel lavoro commissionato c'è tanto da imparare sugli aspetti tecnici, sulla gestione dello stress, sugli altri e su di sè. Mi pare abbastanza. Rinuncio serenamente a una libertà sterile per dare più energia alla ricerca di una libertà molto più complicata ed essenziale.

Per te, cos’è la fotografia?

Uno strumento per conoscere più in profondità me stesso, per entrare in relazione con gli altri e il mondo e in questo lasciare un segno.

A chi passi il testimone?

Grazie Marco per questa intervista. Raramente capita di ricevere domande così pertinenti, interessanti e approfondite. Grazie a Stefano per aver pensato a me.

Passo il testimone ad Angelo Turetta che è un uomo e un fotografo molto speciale.

Grazie.

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

Lorenzo Castore, born in Florence but Rome-based, moves to New York City where he starts his professional career in TV production with Bob Seligman. Back in Rome, he graduates in Law and begins photographing different contexts and places. It’s only after a journey to India and seeing Koudelka’s “Exiles” that he transforms his way of conceiving photography.

In this interview we’ve tried to explore his vision, as characterized as it is by an extremely intimate approach to the things and situations he shoots.

Let’s start with portraits. Do you choose their subjects or are they on assignment, too?

There are portraits and there are portraits - the one I choose for myself and the assigned ones. The latter are per definition commissioned by somebody else. There’s nothing wrong with them - it’s just that they have a different origins than the one I want to accomplish. Then again, apart from very few exceptions, I never mix my work to assignments. I don’t know why, but it’w always been like that. It’s not an ideologic reason. Indeed it’s very personal and it’s not even that clear to me. Let’s just say that I find myself at smoother sailing.

How do you approach them? How do you build the portrait up? Could you give us an example?

The subjects I’m interested in have a magnetic force within.

It’s an attraction that grows gradually - and, in the most striking cases, it turns into a sort of obsession.

The other (the portrayed) subject determines our relationship as much as I do. It’s a mutual thing, and so it always becomes diverse and mysterious. The only fixed variable is an intuition that generates mutual curiosity and reveals hidden affinities. It’s a kind of chemical reaction. I could tell you about Ewa and the first time I saw her. It was on a streetcar. I couldn’t take my eyes off her. She frightened and attracted me at the same time. I wanted to approach her, but I felt goofy and uncertain about the approach. When I discovered that she lived on my same street I just wouldn’t but walk around her for a good two years - without receiving the slightest sign of interest from her. When I approached her, she’d turn me away in disgust. She didn’t want to know a thing about me or my photographs. Then, thanks to Ludmilla - a dear friend of mine to whom Ewa would sell old photos taken by his father - I managed to establish a first approach, which later developed into a years-long relation. I started to take her pictures, I got to know her brother Piotr, we spent lots of time together, and we remained close to each other until the end. Ewa died last December.

I think the most important feature of my portraits is the energy I put in them, being close to [their subjects] yet maintaining some grade of inevitable detachment - no matter how small. If you look at yourself in the mirror, you can’t really do it if you keep your nose onto it - we wouldn’t see anything any longer.

Your photography leaves us with a feeling. It seems like it’s participates of the situations you’re experiencing, as though things - humans included - were given themselves to you for an instant, because you belong to that instant. It seems like they give back your presence on the scene. How do you stay within a scene? How do you move around it?

I don’t know. I’m just there. I try to. I don’t think of the photography, but I try to empty myself - and be there forgetting about myself. [It’s about] being invisible and present at the same time. When this happens in the deeper way, then I happen to lose track of time. I had answered this question more thoroughly, but then I erased most of it - I feel decency in trying to explain certain things that are so delicate and imperceptible. Being in a scene is the way to manifest your own presence, and it’s a physical feeling: I’m a highly physical person, and to me photography is a very physical discipline.

You can find several things within your photos: the suspense (something is going to happen), the freeze of an instant that makes it seem unique, instability, evanescence - like in Ewa&Piotr. All these elements characterize your photography distinctively. They are subtle, liminal dimensions. Is it so? Is this what you’re interested in capturing?

Yes, I’m definitely interested in all that you’re saying - and many other things, too. [I’m especially fond of] what creates tensions, opposites that dwell together, and what I don’t understand and which I can’t really focalize… Belonging to something that attracts and repels you, and trying to approach it… Feeling part of something that is everybody’s and suffering from an intimate isolation at the same time.

Life is really a marvelous thing - not because it’s beautiful (when it is so, indeed), but because it’s a mystery from which revelations might spring out, if you’re lucky.

It’s hard to discuss these things because they’re subtle and you immediately turn too dignified. People will assume you’re presumptuous or cheaply philosophical, and I’d rather avoid that. After all, truth lies in actions rather in words.

How do you choose your stories?

Just like the subjects of my portraits. It’s the same thing.

Could you tell us how you prepare your work on an operational level?

There isn’t a method really - at least, I don’t think I have one. Something happens and when it effects me so massively I try and follow that something and that strong impact. This happens all the time, but the “how” is always different. I’m quite convinced of the importance of being “amateurs” - specialization and professionalism are not my thing. I don’t like knowing what I’m doing too much. It bores me very quickly and then I’ll lose purpose. Obviously I’m referring to the more personal work, not to assignments - which are an entirely different thing. [Assignments] deal with the job and a client requesting a specific work. Anyway, some photographers produce their best works on assignment and follow a strict method, which is always the same and makes them do beautiful things.

There are no absolute rules. Everybody has their own rules and I suppose you’d better stick to them once you’ve found them and [realize] they work for you - unless necessity calls for a change.

Your photographic works seem to constantly let emerge the themes of identity, places and people, and in some cases the subject matter is declared explicitly - we’re thinking of Ultimo domicilio and Sogno #5. Is that so?

Identity, places and people are the common denominator to the whole of mankind. Identity is probably the most 'bright' matter amongst the three you pointed out, but - however ordinary - it’s necessary to stress the fact that identity cannot exist without places and people. Each human being’s ways are tension - right, wrong, failed, successful, empty, structured, conscious, unconscious, original, homologated and so forth - towards the search of their identity.

It’s something we all try to do one way or the other, but you know… Intentions are good, but when it come to facts it’s a different thing altogether. I’ll give a couple of examples in reference to the works you quoted.

The origin of Ultimo domicilio goes back to 2008. I was in Sarajevo and Mostar because the thought of my first experience as a “professional” photographer kept coming back to me - that is the two months I spent between Albania and Kosovo in 1999.

That was an unforgettable experience in terms of the intensity, violence and rapidity I had to confront myself with as I tried to do what I wanted, and [face] the real world, too. As soon as I returned home I’d promised myself I wouldn’t go back to ardent zones where the media covered relevant facts - in general, I was disappointed at the manipulation of the news, the impossibility to really understand what was happening. Plus, I was disgusted at the feverish and bloodthirsty approach of a certain kind of journalism.

My unrest was also connected to the fact that my desire for self-affirmation was something I was familiar with myself, and I didn’t want it to overpower me.

Over the years, the desire of going back to those area did grow (even though I ended up in Sarajevo and Mostar, not Kosovo). I went in search of homes that had been abandoned during the war and never re-inhabited - homes that were left behind overnight together with all the personal belongings identifying their dwellers. I wasn’t looking for desperate stories, but homes that were at least still semi-intact or carrying some sort of presence and a story. It had been nine years since my last visit there and it wasn’t easy to find what I was looking for. The war and siege had changed manifold things: families were forced to migrate and their homes had been distracted - sometimes they’d been rebuilt, whereas others they’d been abandoned for good. [I was seeking] little, insignificant stories that nobody was interested in.

However, Ultimo domicilio hadn’t been planned. I wasn’t working on it. I had travelled to Bosnia because I wanted to confront with what I’ve just said and nothing more.

Then a few months later I was at my place in Krakow and after hanging out the laundry by a ceramic stove, just under the intense gaze of a couple from a vintage photo I’d found at a flea market… It was right then and there that a number of things shaped up. Suddenly, associations [of ideas] came to life, something revealed itself and so I decided to start working on this project knowingly.

The following year I sold that house and left Krakow. That was my only true home, or at least the only home I perceived as such. Before leaving, I barred myself in it for two weeks, I emptied and photographed it all. Everybody’s life is filled with imperceptible wars, and certain world that have been built through love and planning, keeping objects and memories that shape up our identity are destined to be left behind and disappear. I’m saying this with no nostalgia - that’s how things go, and it’s only fair to carry on. Still, it’s important to have something beautiful to remember.

As for Sogno #5, it’s a completely different story, yet very similar at the same time - but I won’t go in too much detail because I’ve already drawn out enough.

This work questions mental sickness/health and the coercive power of institutions, but also the bipolarity within relations and escaping - at least, that’s what it means to me.

What I mean is that it’s obviously about identity, places and people, but the steps to reach out to things are impenetrable, and they have a lot to deal with being careful. You must watch out for the signals we receive from the outside and the inside, rather than being smart and/or clever makers of a beautiful idea as soon as you think you’ve nailed something that works.

It’s the real experience of a job that makes it special.

These places often carry the testimony of something that happened - see Sarajevo/Mostar (from “Ultimo Domicilio). What’s the research or allure that draws you to these places?

I think I’ve answered this question in my previous reply.

I could add that I’ve searched for these homes for months from Italy, without reaching any significant result. Then I contacted a foundation related to the East West Theatre Company of Sarajevo, but I didn’t gain anything either. So I went there and the friend of a friend, Nedim Zlatar, showed me a house he was helping to sell to a French acquaintance - a musician like him. During the following days he took me to Mostar. He and some guys would go to this abandoned cottage there to play. For some strange reason, the electricity company had forgotten to cut the electricity off, so they’d go and rehearse for free as they could plug their instruments and boosters. One day there was a short circuit, a small fire outbreak, and the whole electric system went to pieces. What pushed me to go and search in Bosnia was a reflection, a need linked to something from the past. What really allowed me to find what I was searching was music and a story rich of the present tense. Experience is full of surprises.

You often use motion blur, blurring, slight asymmetries, underexposures - it doesn’t matter whether they’re released ad hoc or subsequently. For instance, we can find them intensely in Paradiso/Avana, Cuba and other works, too. Why do you choose this type of shot?

I think Paradiso has influenced my work a bit too much. I suppose it’s because it was my first work that gained a certain success.

In that case I wanted to shoot in color, and I didn’t want colors to be decorative or descriptive - rather, I [wanted them to be] an active part of the photograph. It’s really a study on color, on the color I’m interested in. It seemed to me I had seen few photos in color that I actually liked up to that day. Then I discovered beautiful things, but in those days color photography seemed pretty useless. Plus, I was 28 and my opinions were stricter and less in-depth than now. They’d described to me the light of Havana’s traffic lights, and I guess that was the main reason I decided to travel.

I wanted to try and make some pictorial photography, so I’d stroll around all night every night in order to catch certain colors and capture those marvelous traffic lights - and at night, with that light, it’s inevitable to stumble upon a certain motion blur, and it was just fine.

I once tried to move the camera while I was shooting to create that effect, and I instantly felt like a complete fool - I still get embarrassed at thinking of such idiocy. Ever since then I’ve always tried to keep my camera as still as possible, even though I haven’t given up shooting at a quarter of a second, if necessary. What I mean is that to me style is quite of a dated problem - I’m much more worried about the energy I use and that comes back from what I do. I don’t believe I’ve ever thought about having to do something in order to resemble my style. In terms of commercial success, I suppose this has damaged me a little (especially after Paradiso and until some three/four years ago), because the public wants to know what they’re going to see and who does what. To know that you’re going to see this or that photographer gives you certainties and reassures you, it creates “idols” and feeds the whole industry. Today things are going better because I think the puzzle I started assembling twenty years ago is becoming even more understandable to whom loves to divide my world into boxes and categories.

I try to avoid everything that will make me look like a caricature. I’m neither the motion blur nor the color or black and white guy, nor the Holga or Leica chap - and I’m not the one from Poland or god knows where. I’ve done and I do many things, one by one, with all the care and uniqueness that each thing I commit myself to deserves for itself.

Could you tell us why you embarked on the Ewa&Piotr - No Peace Without War project?

I met Ewa and she made the strongest impact on me. Once we had finally been introduced, she invited me to her place, and there I got to know her brother Piotr. We started hanging out, getting to know each other and love each other. Over the years, pictures from their past emerged - mostly taken by their father, who had died shortly before they went back to living together. I’ll answer you with a few lines I wrote when I asked myself this same question.

Why do all this?

For the sake of non-sense, to share a human experience, not to judge,

for unexpected beauty, for the pleasure of identifying yourself in a whole,

to realize once more that you don’t do anything for money,

for what we ignore and we can’t talk about.

Ewa and Piotr’s family was well-to-do, but then they lost everything.

Many reasons led to this, but I don’t want to give away too much,

I don’t want to tell their real story with my words or through my rational interpretation.

There are photos from their childhood, my photos from our time together, and a film

(co-directed by Adam Cohen) which doesn’t clarify anything, doesn’t reveal facts -

a film where Ewa and Piotr talk and say what they want and answer however they wish.

For the sake of reinventing, because truth isn’t literal, but absolute and everywhere.

The story of a world in two rooms. Some story.

Ewa and Piotr are able to laugh and make you laugh, they’re cultivated, elegant and sensitive.

They’re not pathetic. There’s only one life, and sometimes it’s strange.

Piotr says it’s not.

You use both color and black and white. What does the choice of one over the other depend on? Is it connected to specific themes or occasions?

I think [it depends on] both. I usually shoot in black and white, but I prefer color in specific cases.

How do you relate to narration?

First of all, I’d like to do it better. For the rest, it’s a very open theme for me. When it comes to photography, it has to do with exhibitions, books and displays, whereas for motion pictures it’s got to deal with the meaning of editing, and the weight you want to give to words and sound. These aspects are all very close, but they imply different points of view in order to fuse everything into one. It’s important to be clear without being banale, to communicate without saying too much. As for how to achieve this, every time it’s an epiphany - or an abortion.

You use cinema as a means of expression, too. Comparing it with photography, what does it offer to you that’s different and what do you think they have in common? (We want to stress the fact that your movie production alone would need an interview per sé, especially for the Ewa&Piotr work).

To me the whole question resolves around the best way to recount what I need to communicate. Photography and movies are means, tools - not a religion. Had I had the talent, I’d have preferred to do music over everything else. It’s by far my favorite art, but I’m so bad at it that over the years I’ve tried to address my alleged talents toward what I felt like and needed to do in order to communicate and share. It all starts here. I don’t really care for the status of photographer or whatever, at all. Therefore I feel free to use the language that seems more appropriate in relation to the content I intend to convey. Plus, movies allow me to use words, music and sound. I’d love to continue making movies so long as I’ll have ideas that seem worthy of time and focus - both mine and others’. There’s a film I’m longing to make, but for contingent reasons I have no more time at my disposal. It’s a kind of documentary for which everything’s ready to be shot, but unfortunately I’ve no funds to finance it further. I’m sure it could turn out to be a beautiful thing - demanding, of course, but I’d be ready to to anything for it. Instead I can’t do it right now, and this generates a deep feeling of frustration. Movies cost so much that even though there’s a big budget, it’s not really big - plus, you need someone to manage the economical relations with the movie industry. Although on a smaller and different scale, this applies for a more anarchic and independent film, too - if not more.

Back to your question… When it comes to movies, you need to be more precise, you ought to be even more clear-minded about what you intend to do, even though the movie might take an unexpected form.

Photography is more ambiguous. You do team-work on movies, unlike in photography. However, the main problem is always the same: you must have something to say and find the way to express it as close as possible to it.

Following in the previous question, we know you enjoy music and painting a lot. How do they influence you as a photographer? What sort of relationship do they establish with your photos?

Music is so ever-present in my life that I could answer this question only by reverse, that is… How much would it influence my life if I had to give it up? - And I’d rather not think about it. As for painting, some pictures have stunned me deeply and I carry them with me over the years. It’s those images that stick to your memory and settle in. They work like certain pictures of books or real facts on me. Everything gets meshed up and becomes its own root, a very personal North Star.

The practical result in my photos lies in the fact that I constantly try to recreate certain images - both consciously and subconsciously -, and I’m not referring to their mere formal aspect.

Do you have any experience with multimedia works? What’s your opinion on these forms of interaction?

I wouldn’t know, I’m not a big multimedia or new technologies expert. I’ve had my website for just a month. I don’t have Facebook, nor Twitter. I still use film for my work. I hold nothing against new technologies and social networks - actually, I think they can be helpful if they’re used properly, but I wouldn’t know how to do it.

With regard to the use of hybrid techniques to create multimedia projects, I think it should be functional to the object of the narration - not smoke in your eyes.

What’s the relationship between your approach as we know it and the photography market? What’s the extent of the freedom you have - or that you give yourself - when you’re working on assignment?

I try to have as much time as possible to work on what’s dear to my heart. In order to do so, I must earn, and i try to earn in any dignified and possibly fast way - so as to have more time and resources to use on my own projects. All my sources of income are occasional and flighty, but for better or for worse it’s always worked out like this so far. I sell for collections (yet not as much as I wished), I run workshops, I do corporate or advertising jobs sometimes, or portraits and small editorials - for years I’ve also been quite regular with working on the documentation of the of big works in progress by important architects. I’ve done the same with the demolition of major public works. In the last few days I’ve taken up the reorganization of Luz, a photography agency we’re trying to transform into a more contemporary - and hopefully more innovative - structure. I told you, specialization doesn’t work for me.

I try to be flexible in order to adapt to the times and have as much time as possible for what’s really important to me.

There’s so much to do for my personal work that when it comes to assignments I don’t ask for freedom if they won’t give me any - and, most importantly, I wouldn’t know what to do with it. There’s a client who wants something, therefore if I accept what he asks for I try and do the job in the best possible way. Otherwise I’ll just decline the assignment. Nobody forces me accept. I’ve no energy to waste on crusades against things that don’t interest me. Moreover, working on assignment makes you learn a great deal on technical aspects, stress management - both on others and yourself. I guess that’s enough. I gladly give up a sterile freedom in order to convey more energies on the search of a much more complicated and essential liberty.

What is photography to you?

It’s a means to know myself more deeply, to enter into relating with others and the world - and, in this sense, leave a mark.

Who do you pass the baton to?

Thank you, Marco, for this interview. It seldom happens to receive such spot-on, interesting and in-depth questions. Thank you, Stefano, for thinking of me.

I pass the baton to Angelo Turetta, a very special man and photographer.

Thank you

- Phom

The articles here have been translated for free by a native Italian speaker who loves photography and languages. If you come across an unusual expression, or a small error, we ask you to read the passion behind our words and forgive our occasional mistakes. We prefer to risk less than perfect English than limit our blog to Italian readers only.

Leave a Reply