Fotografo professionista dal 1988, Stefano De Luigi è membro dell'agenzia VII, vive a Parigi. Le sue immagini vengono pubblicate su grandi magazine internazionali, come Stern, Paris Match, le Monde, Time, New Yorker, EyeMazing, Geo, D di Repubblica, Internazionale. Ha inoltre ricevuto prestigiosi riconoscimenti, tra cui diversi Word Press Photo, il POY, il Leica Oscar Barnack.

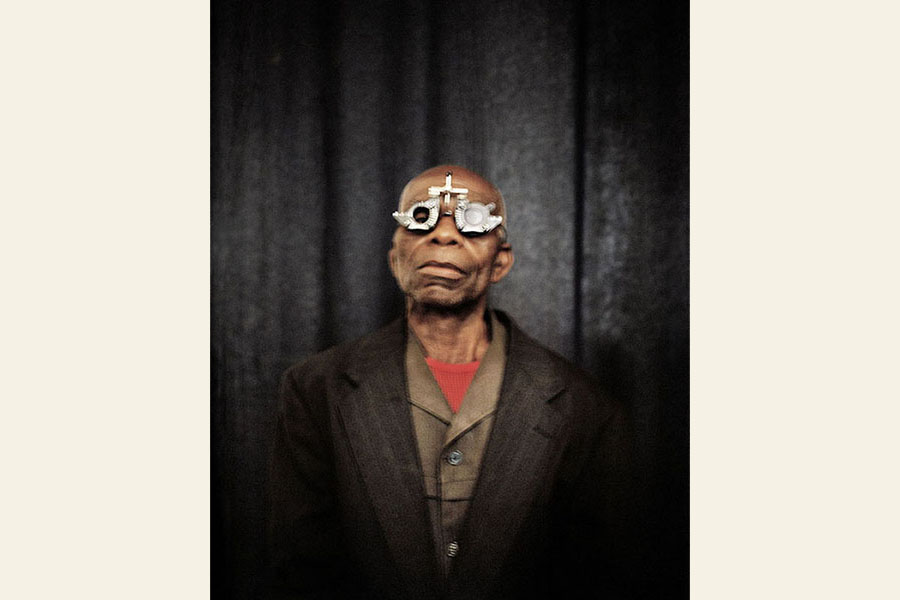

Dal 2004 al 2006, in collaborazione con CBM Italia, produce il progetto Blindness sulla condizione della cecità nel mondo, un lavoro di grande intensità e ricerca visiva. Nell’utlimo suo progetto, iDyssey, realizzato con due iPhone, va alla ricerca delle radici del mondo epico nel bacino del mediterraneo, cogliendone al contempo i segni della contemporaneità.

Nella nostra intervista, De Luigi si racconta, e approfondisce la costante ricerca che compie con la sua produzione fotografica.

Iniziamo da Blanco, il tuo lavoro sulla cecità. Ci sembra un lavoro che mette in atto un’operazione particolare nei confronti di chi guarda: sembra una sfida alla nostra percezione visiva, sottoposta ad un continua “messa a fuoco” e ad una sua ricalibrazione. È così? Cosa ci puoi dire?

Blanco è un lavoro che vuole far riflettere su una condizione umana. La fisicità della cecità è raccontata nel libro attraverso degli elementi di contorno. Come i non vedenti "investono" il loro spazio di vita, come lo occupano, come sono a volte in difficoltà ma anche a loro agio.

Il lavoro vuole però essere anche un’occasione di riflessione sulla metafora del non vedere, "loro che dotati di vista però non riescono a vedere". Per questo mi son permesso di mostrarlo a José Saramago, dal cui libro "Cecità" ho tratto enorme ispirazione. Gentilmente ha acconsentito a che io usassi degli estratti, delle pillole del suo libro, per puntellare questo lavoro, per dargli una direzione che aprisse ad una riflessione più universale sulla condizione del non vedente.

Molte volte, durante questo lavoro mi son sentito scoperto, visibile e identificato dai non vedenti, molto più spesso di quanto mi capiti con i vedenti. Risiede lì la bellezza del lavoro che faccio, le sorprese sono infinite.

Poi più classicamente, il mondo dei non vedenti, è sempre stato oggetto di inchiesta per i fotografi, credo rappresenti, solo superficialmente, la nostra identità speculare, ciò che è all'antitesi della nostra esperienza del guardare vedendo... ecco, non sono il primo ad aver lavorato su questo tema.

Da dove nasce quindi Blanco, da quale urgenza?

Non credo ci sia stata urgenza nel processo che è alla base del lavoro, semmai coscienza. Una felice alchimia di momenti giusti.

Una certa maturità, una certa arroganza, una certa solitudine, che si sono combinate bene ed hanno creato un precipitato che ha dato come risultato un lavoro molto ricco, sicuramente il più importante lavoro che ho fatto e probabilmente tale rimarrà anche in futuro.

Di questo lavoro ne hai fatto una mostra, un multimedia e un libro. Tre media e linguaggi diversi per raccontare, o farci entrare, in un mondo particolare. È una scelta pensata sin dall’inizio o si è costruita nel tempo?

A cosa corrisponde questa scelta, perché articolare con mezzi diversi lo stesso tema?

No, è una scelta dovuta alla rivoluzione del linguaggio fotografico, alla ricchezza del lavoro, alla sua dimensione direi esaustiva, che mi ha permesso nel corso del tempo di poterlo declinare sotto forme e linguaggi limitrofi. Tutto questo non sarebbe stato possibile se il tema stesso non fosse stato così preponderante.

Il contrasto in se stesso era già molto attraente... poi si debbono trovare altre persone che vogliano mettersi in gioco di fronte ad una sfida abbastanza complessa. Io ho avuto la fortuna di incontrarne alcune. Persone coraggiose, o semplicemente giovani che hanno però colto l'opportunità che tale progetto poteva dare loro, in termini di approfondimento.

Che rapporto hai stabilito con i non vedenti presenti nelle fotografie, anche nelle diverse fasi del lavoro, considerando inoltre che la copertina del libro è in braille?

Non c'è molta differenza nella pratica con cui stabilisco generalmente le mie relazioni con i soggetti dei miei lavori.

C'è sempre un equilibrio, direi critico, tra l'empatia e la cordialità , che per me sono i sentimenti motore. Come tutti i fotografi mi dibatto sempre in un limbo che non ho il permesso di oltrepassare, che mi permette di stabilire quella distanza necessaria a riflettere, mentre vivo e consumo l'esperienza della conoscenza, restando però vigile sul momento critico che si deve consegnare con le proprie fotografie.

La sintassi del racconto che non permette buchi né distrazioni, un esercizio molto difficile che si può ottemperare solo con molta pazienza, concedendosi - se si ha la possibilità - il maggior tempo possibile per approfondire.

La scelta di farne un progetto, per me capitale, è venuta seguendo la logica di quello di cui ho scritto prima: con il tempo.

Che tipo di reazioni hai avuto a questo lavoro fotografico, tra il pubblico così come tra gli operatori del settore?

Le reazioni sono state decisamente positive. Il libro è stato molto apprezzato da subito, come un oggetto speciale, per la forma ed i contenuti. Il multimedia ha avuto come il libro diversi riconoscimenti e per via della sua facile fruibilità è stato visto in una proporzione immensamente maggiore del libro o della mostra. Ciò mi conforta riguardo alle scelte che ho fatto, di declinare il lavoro con diverse potenzialità di fruizione.

E' ambiguo il rapporto che si ha con un progetto personale. Una volta finito, si è felici di essere liberi dall'ossessione . Allo stesso tempo la sovrastruttura professionale mi impone (per fortuna) di cercare di raggiungere i più con la divulgazione del mio lavoro.

I tuoi lavori - visti nel complesso - sono caratterizzati da una molteplicità di mezzi e forme: digitale, smartphone, panoramica, uso di diversi mezzi nella diffusione del lavoro. A cosa corrisponde, nella tua ricerca personale, questa varietà di strumenti?

Corrisponde ad una curiosità personale che è il motore del mio vivere.

Le opportunità di arricchire il linguaggio fotografico, che siano esse determinate da un progresso tecnologico o da un sapere artigianale profondo, mi spingono a riflettere sulla ricerca, sulla sperimentazione.

La discriminante rimane l'onestà intellettuale del fare uso di questi mezzi solo quando un motivo valido li sostiene. In altre parole: non appartengo alla schiera di ortodossi che rifiutano per principio le novità, né a quelli che hanno determinato il loro stile e si attengono a delle consegne estetiche che sono la loro carta d'identità d'autore. Cerco di tenere aperta la porta a delle novità che possano sedimentarsi nel mio lavoro, sempre però cercando prima di tutto di rispondere alla domanda: perché lo sto facendo?

In particolare, il tuo ultimo lavoro iDyssey è realizzato interamente con uno smartphone. Ci puoi dire il perché di questa scelta?

Gli smartphone hanno modificato parte del linguaggio che io uso per esprimermi. Da qui nasce una curiosità direi insopprimibile, di andare a vedere cosa succede. Ma gli smartphone, pur amplificando la veicolazione di immagini, l'uso della fotografia e la sua fruizione, portano con loro una pericolosa nozione: la superficialità. Lasciando alla macchina un potere enorme, si è fatta strada l'idea che la modalità "random" insieme ad una buona applicazione potesse produrre delle buone fotografie. Fotografie accattivanti, ma molto superficiali.

Il senso ultimo di iDyssey è ribadire che una buona fotografia veicola un pensiero, una buona fotografia ci interpella continuamente, una buona fotografia non ci spiega e non si spiega immediatamente. Che sia fatta con una scatola di scarpe o con l'iPhone il concetto rimane lo stesso.

Poi, il motivo per cui ho usato l'iPhone (due) per questo lavoro è che volevo raccontare l'Odissea, che insieme all'Iliade è l'eredità culturale più antica del mondo occidentale, con il più moderno dei suoi media. Io sono sempre un cantastorie, ma contemporaneo...

Il tuo sguardo cambia quando fotografi con uno smartphone? E se si, come?

Non è il mio sguardo a cambiare, semmai uno stato d'animo direi più leggero e avventuroso.

Per due mesi ho viaggiato con ogni mezzo di trasporto, con la felicità estrema data dall'essere riuscito a sbarazzarmi degli orpelli professionali, per rimettermi in gioco come agli inizi del mio lavoro. Ed essere riuscito a fare questo viaggio che tanto volevo fare, ma trovando il vero motivo per farlo. È stato liberatorio. In questo senso il mio sguardo era diverso, più libero di spaziare oltre il perimetro che di solito si definisce nel raccontare le storie.

Qui erano la Storia, gli uomini, i luoghi, il passato, il presente a giocare continuamente davanti ai miei occhi.

Guardando iDyssey sembra di osservare un recupero di una certa matericità dell’immagine, che si differenzia da una certa perfezione del digitale. È così?

Si è così, l'impressione è stata quella di tornare a scattare con l'analogico per esempio, perché inquadrare e scattare con il telefono è un'operazione per me più lenta, che richiede la stessa concentrazione dello scatto singolo delle Leica, ed il risultato tecnico nella sua "impura materialità" si apparenta molto alle stampe analogiche.

Che distribuzione ha avuto iDyssey?

iDyssey ha avuto una prima distribuzione editoriale, un magazine in particolare ha avuto il coraggio di sostenere il progetto dall'inizio, Geo France, poi via via gli altri sono arrivati, il New Yorker ha voluto creare un multimedia a partire dai corti che avevo girato e le registrazioni di suoni prese lungo la strada. Ora il progetto sta avendo una seconda vita con alcune mostre realizzate: è già stato presentato alla Fondazione Stelline di Milano con il sostegno del Piccolo Teatro, a Parigi per il Mois de la Photo ed altre mostre in preparazione prossimamente.

Anche qui ho tanto materiale magmatico su cui poter lavorare e gli incontri che sto facendo mi fanno essere ottimista sulla vita di questo progetto.

Un lavoro come T.I.A. lo avresti realizzato con lo smartphone?

No, perchè come ho spiegato mi pongo sempre la domanda: perché lo sto facendo? E per T.I.A. non avrei sinceramente trovato nessuna risposta.

Passiamo a T.I.A.: l’idea di proporlo come dittico, almeno sul sito, da dove nasce? Sembra che la relazione tra le fotografie si appoggi su assonanze formali e/o di contenuto, è così?

Nella presentazione paragoni questo progetto ad una ballata. Puoi dirci in che senso?

T.I.A. è una riflessione sulla lunga vita che le foto hanno indipendentemente dalla nostra volontà. Come queste riescano a volte a dialogare tra loro a distanza di anni, come disegnino una linea che racconta una coerenza nello sguardo, nei princìpi, nel modo di vivere. T.I.A. come ho detto vorrebbe essere una ballata, una forma di poesia dedicata ad un continente che amo, che mi incuriosisce, mi impaurisce, mi soggioga, mi spiazza, mi intristisce, mi rigenera...

Nell'impotenza accettata del non poter dire una parola definitiva dopo oltre 20 anni di lavori in Africa, ho voluto almeno creare dei capitoli, una specie di riassunto personale delle mie esperienze, umane e professionali, dittici che cercavano di identificare alcuni aspetti preponderanti delle società africane e dei movimenti geopolitici, economici che ho raccontato con tanti reportage in quel continente.

Non lo considero un progetto finito ma so anche che sarà difficile, e difficile è un eufemismo.

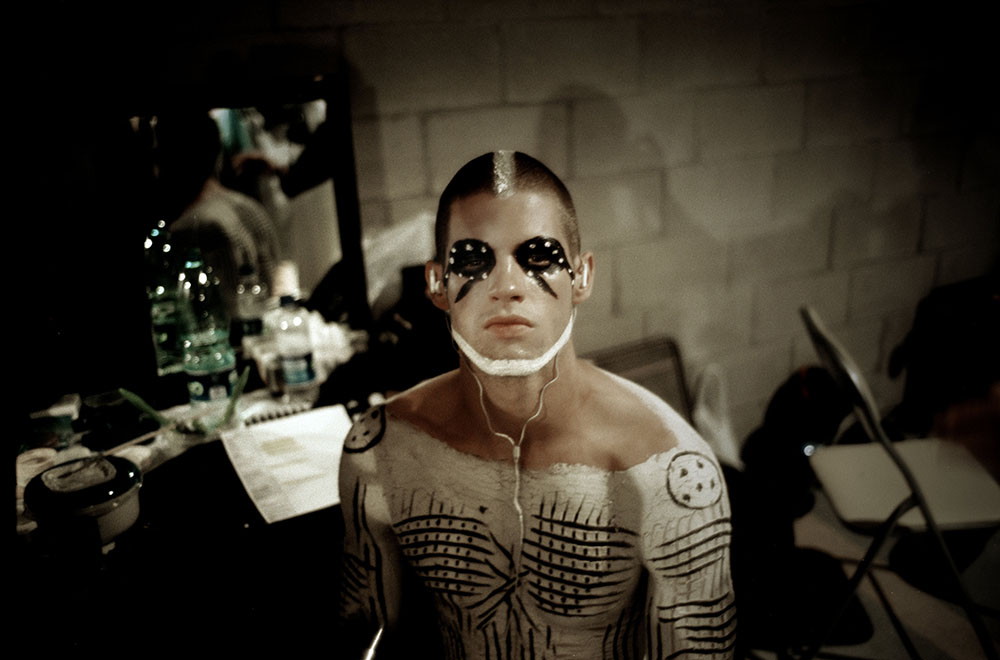

In una parte della tua fotografia sembra esserci un rapporto con il cinema che si esprime nella luce di molte tue immagini. Oltretutto al cinema hai dedicato un lavoro Cinema Mundi. Ce ne vuoi parlare?

Si, il rapporto con il cinema è quello di un innamorato. Da sempre, sopratutto grazie agli anni trascorsi a Parigi e adesso che sono tornato a vivere in questa città il rapporto con il Cinema mi è sempre sembrato fondamentale. Un rapporto da fruitore, da semplice viaggiatore che paga un biglietto per regalarsi un magnifico viaggio nella mente di un altro un biglietto pagato per farsi proiettare in un posto dove le fantasie sono sconfinate, come Alice. Da qui una grande influenza nel mio lavoro. E la sensazione che nel corso del tempo si è andata rafforzando che il cinema sia spesso un susseguirsi di still, di fotografie. Attraverso i film ho studiato anche la luce, non in modo programmatico ma d'istinto. Poi credo nel corso degli anni, come capita a tutti, i miei gusti si sono affinati ma resto un consumatore spesso onnivoro in fatto di generi.

Guardando i tuoi lavori emerge come spesso sai esprimerti con registri stilistici diversi. Pensiamo a lavori come Hidden China o Chinese Holidays. Una sorta di eclettismo, che ci sembra parte del tuo approccio alla fotografia. È così?

Si è così, sicuramente è un mio limite perché spesso gli interlocutori di questo mondo vogliono sicurezze, penso in particolare alle gallerie e alle istituzioni. Vogliono dei bei cassetti dove poter sistemare schematicamente generi e stili.

Io ho difficoltà a classificarmi. Uso genericamente il termine Documentary Photographer perché credo che corrisponda più da vicino al senso della mia ricerca. Ma non nego che mi costa a volte prendermi sul serio. Se ho voglia di fare un lavoro che per me è importante o che mi incuriosisce, è difficile rinunciare per via di alcuni paletti che altri miei colleghi sono molto più bravi di me a mettere.

Per i lavori che citi, siamo su due registri diversi che vorrebbero indicare un paese complesso che può offrirci stati d'animo molto diversi tra loro.

C’è un momento del tuo processo fotografico in cui pensi al tuo pubblico?

No, anche perché io non ho un pubblico. Penso alla veridicità delle storie che sto raccontando, penso a non farmi manipolare, penso che quando posto un'immagine su Instagram o anche su Facebook ho una responsabilità prima di tutto con chi leggerà quello che scrivo o vedrà quello che ho scattato, ma nel processo creativo sono sempre stato e sarò sempre in beata solitudine.

Che rapporto hai con la narrazione?

Difficile, perchè non riesco come vorrei ad astrarmi molto spesso dalla realtà.

La narrazione ha bisogno di momenti lirici per poter coinvolgere il lettore/fruitore e molto spesso non riesco a trovare in me questi momenti di poesia, almeno non tanti quanti ne vorrei trovare.

Cos’è per te il fotografare?

A fasi alterne una gioia ed una sofferenza, mai stato qualcosa che mi ha lasciato indifferente, credo sia più facile dire che sia il mio modo di stare al mondo.

A chi passi il testimone e perché?

A Lorenzo Castore, che stimo da molto tempo, il cui lavoro come il buon vino diventa sempre migliore con gli anni.

Grazie

Intervista a cura di Marco Benna

ENGLISH VERSION

A professional photographer since 1988, Stefano De Luigi is member of Agency VII and resides in Paris. His photos are published on big international magazines, such as Stern, Paris Match, le Monde, Time, New Yorker, EyeMazing, Geo, D di Repubblica, and Internazionale. He has also received prestigious awards, amongst which are several Word Press Photo’s, POY, and Leica Oscar Barnack.

Between 2004 and 2006, in collaboration with CBM Italia, he produced Blindness, a work on the condition of the blind in the world - a highly intense project with peculiar visual research. In his latest project, iDyssey, which has been released through two iPhones, he sets on a quest to find the roots of the epic world in the Mediterranean, catching its signs of contemporaneity.

In our interview, De Luigi tells about his story, and deepens the incessant research that permeates his photographic production.

Let’s start with Blanco, your work on blindness. We think it presents a particular take to the viewers: it looks like a challenge to our visual perception, that is subjected to a constant “focusing” and its re-adjustment. Is it so? What can you tell us about it?

Blanco is a work intended to make people reflect on the human condition. The physicality of blindness is told in the book through side elements. How the blind “invest” their life space, how they occupy it, how they sometimes don’t feel at east or how they feel comfortable, too. However, the work is also intended as an opportunity to reflect on the metaphor of not being able to see - “those who do have sight, but are not able to see”. That’s why I dared to show it to José Saramago, whose book “Blindness” was a big inspiration for me. He kindly consented that I used extracts from it - like pills of his book - in order to delve more into this work, and direct it towards a more universal reflection on the blind’s condition. During this work I’ve often felt bare, visible and identified by the blind much more than it happens with the non-blind. That’s where the beauty of the the work I do lays. It’s always been inquired by photographers. I think it represents - superficially only - our mirror identity, what is opposite to our experience of watching by seeing. There you go, I’m not the first to work on this theme.

Where does Blanco originate from? From which urge?

I don’t think there was ever a urge in the basic process of the work - but conscience, rather. A merry alchemy of right moments. A certain maturity, arrogance, solitude that blended together well and lead to a result that is rich. It’s surely the most important work I’ve made so far - and, probably, that I’ll ever make.

You’ve set up an exhibition out of this work, in addition to a multimedia project and a book. They’re three different media and represent three different ways to tell, or let us in, in a particular world. Is it a pondered choice or did it develop with time? What does this choice represent? Why articulate the same theme through several media?

This choice is connected to a revolution in the photographic language, the richness of the job, and its (I’d dare say) exhaustive dimension - which allowed me to decline it under neighboring forms and languages, with time. This wouldn’t have been possible if the theme itself hadn’t been as predominant.

If the very contrast wasn’t as attractive, then you’d have to find other people who’d be up to prompt themselves to such a complex challenge. I’ve been so fortunate as to meet some brave people, or simply youngsters who grabbed the opportunity that such project could give them in terms of deepening the analysis.

What kind of relationship did you constitute with the blind people in your photographs, in the different phases of the work, also considering that the book cover is in Braille?

There isn’t much difference in the way I relate with the subject I work with. There’s always a (I’d say ‘critical’) balance between empathy and kindness, which are the primary feelings for me. Similarly to all photographers, I always find myself battling in a limbo that I’m not to cross, and that allows me to build the necessary distance to reflect whilst I’m living and experiencing that (given) situation. However, I always remain alert in terms of the critical moment you have to deliver through your photographs. It’s about the syntax of the story, that leaves no room for gaps or distractions. It’s a highly difficult exercise that you may achieve only through a lot of patience, allowing yourself as much time as you can in order to deepen [the analysis]. The choice of making it a paramount project followed the logic I described above, and it developed over time.

What was the reaction of the audience and the experts to this work?

I’ve had extremely positive reactions. The book was appreciated at once, and regarded as a special project for its form and contents. Similarly, the multimedia has gained various acknowledgments and, because of its easy usability, it gained much more exposure than the book or the exhibition. This reassures me as to the choices I’ve made - to decline the work in different way, with different usability opportunities. The relationship you have with a universal project is ambiguous. Once it’s finished, you’re happy to be over the obsession. At the same time, my professional mind-set (fortunately) forces me to tend to more and more ways of spreading my work.

On the whole, your works are characterized by a multitude of media and forms: digital, smartphone, panoramic pictures, and the use of different ways of distributing the project. What does this variety of tools represent for your personal research?

It matches a personal curiosity, that is the fuel to my living. The opportunities to enrich the photographic language (be them determined by the technological process or by an in-depth artisan knowledge) push me to reflect on the research about experimentation. Still, one discriminant remains: that’s the intellectual honesty to utilizing these means when there’s a valid motif behind. In other words, I don’t belong to the Orthodox line of photographers who refuse innovation for a question of principle. Neither do I belong to the group of photographers whose style has been determined by it, and who stick to aesthetic assignments as their authorial ID. I try to leave the door open to innovations that may sediment in my work. But first, I’ll always try to answer the question: “Why am I doing this?”.

In particular, your latest work, iDyssey, was entirely made with a smartphone. Could you tell us about this choice?

Smartphones have modified part of the language I use to express myself. Here-hence the birth of what I’d call an ‘undying’ curiosity to check on what’s going on. However, smartphones - although they amplify the distribution of images, the use of photography and it’s fruition - carry a dangerous concept with them, that is superficiality. Leaving enormous power to a device has lead to thinking that random mode, in addition to a good app, can produce good pictures - catchy pictures, but superficial. The ultimate meaning of iDyssey is to stress the fact that a good photograph conveys a thought, it talks to us constantly, it doesn’t self-explain itself and it’s not unveiled immediately. The concept doesn’t change, regardless of whether the picture is taken with a shoe-box or an iPhone. The reason why I used two iPhones to shoot this work is that I wanted to tell of the Odyssey (which is, together with the Iliad, the most ancient cultural heritage of the Western civilization) through the most advanced medium. I’m always a storyteller, but a contemporary one…

Does your sight change when you’re shooting with a smartphone? If it does, how?

It’s not my sight that’s changing, but rather an inner feeling - that I’d say is lighter and more adventurous. For two months I travelled on any means of transport and in great happiness, because I’d managed to get rid of the professional frills, and I challenged myself again like at the beginning of my career. [I was happy also because] I had managed to finally venture on this trip I had longed for for a long time, but failing to find a real reason to do it. It was freeing. In this regard, my sight was different - more free to wander beyond the perimeter that usually defines us whilst telling stories. Here History, men and women, places, the past and the present were playing before my eyes.

Looking at iDyssey it feels like observing the return to a certain materiality of the picture, that is different from a certain digital perfection. Is that so?

Yes, it is. For example, the idea was to going back to shooting analogically, because framing and shooting with a smartphone is a slower operation for me, which requires as much concentration as a single shot with a Leica. And the technical result, in its “impure materiality”, is very similar to analog prints.

What distribution did iDyssey get?

First came the editorial distribution. One magazine in particular (Geo France) had the courage to support the project since the beginning. With time, came other magazines such as the New Yorker, which wanted to create a multimedia project commencing with the short films I had produced and the recordings of sounds taken from the street.

Now the project is having a second life through exhibitions in Paris for the Mois de la Photo and other upcoming exhibits. In addition, it’s been presented to the Fondazione “Le Stelline” in Milan, with the support of the Piccolo Teatro.

In this case, too, I’ve got a lot of magmatic material to work with, and the current meetings I’m involved in make me feel optimistic about the life of this project.

Would you have produced a work such as T.I.A. with a smartphone?

No. As I said before, I always pose myself the same question: “Why am I doing this?”. And, quite frankly, I wouldn’t have found any answer for T.I.A.

Let’s move on to T.I.A.: what’s the origin of the idea to showcase it as a diptych on your website, too?

In presenting this project, you compare it with a ballad. Could you tell us in what way?

T.I.A. is a reflection on the long life of photos regardless of our intention, how they are capable to produce debate after years, how they trace a line that tells of a coherence of sights in principles - and on the way of living. I said that T.I.A. should have been a ballad, a kind of poem dedicated to a continent I love and makes me curious - a continent that scares, overpowers, puzzles and saddens me, and regenerates me, too.

Accepting the impotence to speak a definite word over 20 years of work in Africa, I wanted to at least create some chapters, a sort of personal recap of my experiences, both personal and professional… [In other words,] diptychs trying to identify some of the most characterizing aspects of African societies, and geo-political and economical movements I recounted with many reports in that continent.

I don’t deem it finished, but I know it’ll be a difficult project - and “difficult” is just an euphemism.

In part of your photography there seems to be a relationship with the movie industry, expressed in many of your pictures’ light. Plus, you’ve dedicated a work, Cinema Mundi, to the film industry. Could you tell us about it?

My relationship with the film industry is that of a person in love. It’s been like this forever, especially thanks to the years in Paris. Now that I’m back to living in this city this relationship [feels even more] important than ever. It’s a bond as a user, a simple traveller who pays the price of the ticket to give themselves a gift - a marvelous mental trip of another ticket paid to be projected in a place where fantasies are limitless, like Alice. Hence a big influence on my work. The perception that’s been sedimenting stronger and stronger over time is that movies are often a sequence of styles and photographies. Through movies I’ve also studied lighting - not programmatically, but by instinct. Also, I believe that it happens to everyone over the years… My tastes have become sharper, but I stay an (often) omnivore consumer when it comes to genres.

By looking at your works it often emerges how you’re able to express yourself in different stylistic codes - our mind goes to such works as Hidden China or Chinese Holidays. It seems to us like a sort of eclecticism that participates of your approach to photography. Is that so?

Yes, it is. Honestly, it’s a limit of mine, because often times the interlocutors in this field are in search of certainties - my mind goes to galleries and institutions in particular. They expect beautiful drawers where they can place genres and styles methodically.

I find it hard to classify myself. I use the term ‘Documentary Photographer’ generically, because I feel it best fits the sense of my quest. But I don’t deny that it’s hard to take myself seriously sometimes. If I want to work on a project that is important for me and makes me curious, it’s hard to give it in because of certain limitations that other colleagues of mine are much better at putting than I am. With regard to the works you cited, we’re on about two different codes, that are supposed to pinpoint to a complex country and deliver highly different emotions to us.

Is there a moment in your photographic process when you think of your audience?

No - also because I don’t have an audience. I think about the truthfulness of the stories I’m telling, not to let others manipulate me. I think about the fact that when I’m posting a picture on Instagram or Facebook I first have a responsibility toward those who will read or see what I’ve shot, but along the creative process I’ve always been - and I’ll always be - in blissful solitude.

What’s your relationship with narration?

It’s difficult, because I felt to abstract myself from reality as much as I’d like to. Narration entails lyrical moments in order to be able to capture the reader/user and often times I can’t find these moments of poetry within myself - at least not as many as I’d wish.

What does photographing mean to you?

It’s alternatively joy and sorrow. It’s never been something that’s left me indifferent. I think it’s easier to say that it’s my way of being in the world.

Who are you passing the baton to and why?

To Lorenzo Castore, whom I have appreciated for a long time. His work, like good wine, gets better as the years go by.

The articles here have been translated for free by a native Italian speaker who loves photography and languages. If you come across an unusual expression, or a small error, we ask you to read the passion behind our words and forgive our occasional mistakes. We prefer to risk less than perfect English than limit our blog to Italian readers only.

Leave a Reply